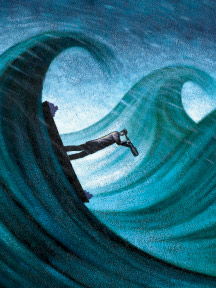

“Zapatero is not a good driver. It’s like a boat, which in calm waters steers fine, but when it gets bumpy, they are not prepared.” The same could be said for many of the world’s C-level leaders, so it’s perhaps not surprising that both companies and countries are finding out the hard way that credit can dry up when the sea gets choppy…

“Zapatero is not a good driver. It’s like a boat, which in calm waters steers fine, but when it gets bumpy, they are not prepared.” The same could be said for many of the world’s C-level leaders, so it’s perhaps not surprising that both companies and countries are finding out the hard way that credit can dry up when the sea gets choppy…

Not a bull in sight as the bears go after Spain

From the nosebleed seats of the E.U., government cries out ‘We are not Greece’

By Barbara Kollmeyer, MarketWatch

MADRID (MarketWatch) — Eduardo Fernandez Agudo is old enough to have lived through other economic crisis in Spain, but the current one has him worried enough.

“We are in a very difficult time. For people, for companies, for everyone this problem is very hard,” said Agudo, a 67-year old Madrid-based engineer who works for building and construction group Volconsa.

He said his company has faced difficulties in getting new contracts for work and much competition for the few offers that are coming in. Spain’s economic crisis has been driven by a collapse in the housing and construction market, which has pushed the unemployment rate to near 20%.

“I see four or five more hard years for Spain with this crisis,” said Agudo, who, like everyone else here has friends or family who have lost jobs. And he doesn’t think the current government led by Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero is handling things well.

“Zapatero is not a good driver. It’s like a boat, which in calm waters steers fine, but when it gets bumpy, they are not prepared.”

Unfortunately for Spain, much of the rest of the world and financial markets share Agudo’s doubts about Zapatero’s Socialist government and its plans to get the depressed economy back on track. Newspapers here as well have dogged the government from across the political spectrum in rare harmonious action.

Under attack is certainly how Spain’s government and markets are feeling these days.

“Objetive: Espana,” in other words, “Target: Spain,” was a headline that ran in politically-centric newspaper El Pais in the wake of last Thursday’s selloff in Spanish stocks, when the IBEX 35Â (INDEX:XX:IBEX)Â suffered its biggest one-day loss since 2008.

That pressure did appear to be easing as of Wednesday, with talk that Germany is working on a rescue package for debt-choked Greece, possibly involving loan guarantees. See Germany working on Greek rescue plans

But speculation on Spain may not be over. “It’s possible that these attacks will continue,” said Jordi Fabregat, associate professor of the Department of Financial Management and Control at the ESADE Business School in Barcelona in an email interview.

Much depends on the government’s ability to implement reforms without strikes or hard opposition in Congress, said Fabregat. “In any case, if investors are not confident in the sovereign debt in Spain, the interest rate of this debt will increase [and] so will the corporate debt,” he said, adding rising rates will hurt equities.

Running from the bull

The government has hustled to respond to the harsh global spotlight.

Spain’s economy minister Elena Salgado flew to London on Monday, not to meet with her British counterpart, but to chat with the Financial Times newspaper, which has been heavily critical of Spain. Meeting with investment banks in London and Paris this week, Secretary of State for the Economy Jose Manuel Campa said Spain will cut its budget further if current measures aren’t enough.

Two weeks ago the government announced a plan to shave 50 billion euros ($69 billion) off the budget over three years to rein in its spiraling public deficit, and bring its debt to GDP down from 11%-plus in 2009, to 3% by 2013, to toe the line on European Union criteria.

The government is also battling to push labor reforms past unions. Zapatero, who announced more stop-gap measures to help Spain’s 4 million-plus unemployed on Wednesday, faces tough opposition from a proposal to hike the age of retirement to 67 from 65.

Spain’s government is also highly decentralized — a reaction to the lengthy dictatorship of Francisco Franco — and controls less than one-third of public sector spending, which means Zapatero will have to reach political consensus with powerful regional leaders.

For markets, the credibility gap lies within the government’s pledge to dramatically cut that debt to 3% of GDP as it faces nearly 20% unemployment, the highest in the eurozone as a result of a collapsed housing and construction market. The government lifted its fiscal deficits by around 2 percentage points of GDP for 2010 to 2012.

“And, as the increase in GDP will remain negative in 2010 and very little for the next years, this deficit will stay for 3 more years above the maximum 3%,” said ESADE’s Fabregat. “This will increase our debt to 75% of GDP. And of course, unemployment of 20% is far above other countries in EU.”

But it’s not like this bad news was a big surprise to anyone here. “Everyone knew where the economy was and that it was going to stay very weak from this year to the next year. The analysts and researchers agree the public deficit was going to be higher than the government was estimating,” said Estefania Ponte Garcia, head of the economy and strategy department at BNP Paribas Fortis in Madrid.

Spain defaulting on its debt, an underlying fear of the market, is not being taken seriously, though another downgrade of sovereign debt ratings is a possibility, economists say.

In rejecting comparisons to Greece, the government argues its debt burden is the least of any of the lower-tiered Europe economies. At 54% of GDP in 2009, it was less than half of Greece or Italy’s and lower than that of Ireland, Britain or Portugal.

“The situation is very different because the quality of the statistics presented by Greece is under scrutiny because it seems that they presented wrong numbers,” said Fabregat.

“Here investors can doubt our capability in reducing costs in the future, but not about the figures we present.”

But there is that high unemployment level, as workers like Agudo battle to keep working and many southern American immigrants return to their own countries, convinced fortunes are better there. Plenty of stories abound about Spanish housewives or “amas de casas” forced back into the job market to support their families.

“We have our problem: that is the very big weight of the construction sector into GDP. Everyone analyzed that it was going to decrease, but not so huge and so quick,” said BNP Paribas’ Garcia. “The main problem is we were a construction economy and it has to change we have to improve our information technology and business equipment investment.”

Red flags for investors

At least one side of investment is set to take a hit with the government’s budget plans. Analysts at Citigroup pointed out recently that several Spanish toll roads could face “material debt refinancing and restructuring challenges,” under government plans to shave 10% off planned infrastructure-related investment in 2010.

That could affect companies such as Sacyr Vallehermos (SIBE:ES:SYV) , Abertis Infraestructuras (SIBE:ES:ABE) and Fomento de Construcciones y Contratas (SIBE:ES:FCC) (OTHER:FMOC.Y) , which own stakes in highways here. That may also hit the Obrascon Huarte Lain-owned (SIBE:ES:OHL) M-12 airport link.

Maria Folque, Madrid-based chief investment officer for Tressis, a money manager for high-net-worth individuals, said they got out of Spain via a pan-European fund last summer after seeing markets move up strongly last year. Spanish stocks are up 20% on a 12-month basis.

“Last year, Spanish markets were the best in Europe…it’s really strange as we didn’t have a rosy economic future, but last year we were seen as a proxy to emerging markets,” she said, noting the connection to Latin America for many Spanish companies.

“But at the same time I think now there are a lot of good opportunities in the Spanish markets,” she said. “The profits of Spanish companies last quarter were extremely good, and lots of them have high dividends.”

Perhaps Santander (NYSE:STD) (SIBE:ES:SAN) can take some comfort from that. The bank had the misfortune to release earnings last Thursday, suffering a more than 9% fall in shares despite upbeat earnings. See Santander earnings story.

Meanwhile life on the ground here promises to get even tougher. “In general terms we will see the unemployment increase the next two years,” said ESADE’s Fabrega.

“Spain needs an increase of 2% in the GDP in order to have a net creation of employment.” Higher taxes are a given, while mergers in the banking sector are expected in order to be able to battle with an increase in overdue mortgages.

“Now the rate of unpaid mortgages is about 5%, but we are afraid that this figure will increase in 2010,” he said.