As Canadians sparred over fake lakes, budget-busting security, and the global capitalist conspiracy, the world’s twenty most influential leaders convened in Toronto this past June to negotiate a response to the worst financial crisis in generations. At issue was an age old debate between two economic philosophies: stimulus as a life vest versus stimulus as a straitjacket. The pro-life camp was championed by consumerist America and its global supply chain. The pro-restraint camp was led by conservative Germany and its regional demand chain. At risk were millions of jobs, trillions in debt, and quite possibly the fate of our modern political economy.

As Canadians sparred over fake lakes, budget-busting security, and the global capitalist conspiracy, the world’s twenty most influential leaders convened in Toronto this past June to negotiate a response to the worst financial crisis in generations. At issue was an age old debate between two economic philosophies: stimulus as a life vest versus stimulus as a straitjacket. The pro-life camp was championed by consumerist America and its global supply chain. The pro-restraint camp was led by conservative Germany and its regional demand chain. At risk were millions of jobs, trillions in debt, and quite possibly the fate of our modern political economy.

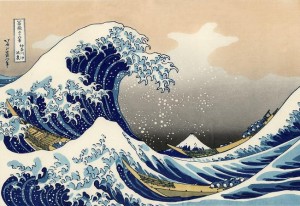

With so much on the line, the G20’s vague and non-committal communique was particularly troublesome, since a crisis this big requires a coordinated and comprehensive response. Instead, the world’s two largest economies spent the weekend channeling their biggest historical fears — a wave of premature austerity in America that prolonged the Great Depression, and debt-fueled German hyperinflation that gave rise to National Socialism and sparked a continental war.

This failure to build consensus might have been expected but it wasn’t inevitable. Stimulators and Austerians already agree that governments, businesses and households have each spent decades borrowing and spending well beyond their means, leaving future generations a legacy of their grandparents’ debt. They are both aware of the structural dangers of excessive leverage, and admit that it was only allowed to proliferate because nobody wanted to take away the punch bowl while the party was still going. Their only two fundamental disagreements involve dealing with the resulting debt hangover and charting the least painful path toward fiscal sobriety.

Coordinating an emergency response was a much easier sell during the global panic of late 2008. Now that most major economies have stabilized, the timing and scale of stimulus withdrawal has evolved from an exercise in economic triage to a debate about theraputic recovery. Exit too soon and we could tip back into recession. Exit too late and a cascade of debt default could fracture the global banking system and plunge the world economy back into the abyss.

To put the G20’s challenge in context, nearly three years after the onset of the recession, America’s economy — the world’s largest — still hasn’t emerged from its slump. Persistently high unemployment has devastated consumer confidence and removed any hope of a quick housing recovery. At the same time, a shell-shocked banking sector has slowed critical business lending. Without a resurgence in demand a viscous deflationary trend will likely cause the nascent global recovery to stall.

Despite these considerable headwinds, the US remains one of the few countries with enough debt capacity to fund another round of stimulus — unlike Japan, Italy, France or even the UK — fueling calls for more shock therapy. The Stimulators are worried about a pulling the plug too quickly, claiming that recessions are the worst possible time for the public sector to retrench. As Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman suggests: “Yes, America has long-run budget problems, but what we do on stimulus over the next couple of years has almost no bearing on our ability to deal with these long-run problems.â€

In contrast, Germany’s economy — the world’s fourth largest — seems to be firing on all cylinders. Unemployment is relatively low and falling, manufacturing output is at pre-recessionary peaks, and a lower euro is helping boost sales to key Asian markets. However, the country’s exporters are still heavily exposed to other struggling trading partners, many of whom are in much worse shape. Moreover, after the trillion euro bailout announcement this past May, Germany’s financial system is now tied even more intimately to the fiscal health of its neighbours. Given years of profligate spending, these sluggish regional economies are now a dangerous liability for the fragile German recovery.

The typical Austerian response calls for a strong dose of fiscal consolidation, trading off near-term economic pain for a more sustainable long-term recovery. Globetrotting economist Jeff Sachs puts the argument in perspective: “It is wrong in this context to believe that the only choice is further fiscal stimulus versus a repeat of the Great Depression. Further short-term tax cuts or transfers on top of America’s $1,500bn budget deficit are unlikely to do much to boost demand, while they would greatly increase anxieties over future fiscal retrenchment.â€

Outside of the irony of capitalist America and socialist Europe swapping policy playbooks, their compromise at the summit did little to resolve the inescapable tension between hair-of-the-dog stimulus and cold turkey austerity. One reason this increasingly popular debate has been so difficult to resolve is that it involves fundamental beliefs about the role of public debt in a free market society.

Put simply, debt allows borrowers to “pull demand forward†and consume today what they would otherwise have to wait to consume tomorrow. Such borrowing can help entrepreneurs start-up businesses, governments build roads and schools, and young families buy their first homes. More recently, however, it has allowed individuals, businesses, and governments in developed economies to consume well beyond their means with little of value to show for it.

Rising American public debt over the last three decades provides a useful illustration. Populist programs like tax cuts, mortgage subsidies, and cash-for-clunkers have predominantly supported retail and residential consumption while the nation’s highways, bridges, power grids, schools and health systems have been left to decay, causing trillions in lost productivity and competitive disadvantage. Similar trends in Europe have pushed some of the region’s more egregious borrowers like Greece and Spain to the brink of default. Had Western governments followed the example of centrally-planned China or emerging Brazil and invested public borrowing in critical infrastructure rather than pet projects or plump payrolls, there might be less debate over the merits of additional stimulus and more to show for trillions in government spending.

After the last double-dip recession in the early 1980s, one of Jimmy Carter’s economic advisers observed that “it is not the wolf at the door but the termites in the walls that require attention.” This time around, both near term relapse and longer-term default represent clear and present dangers to the fledgling global recovery. Additional stimulus will only work if it is strategic and surgical, and austerity only if it includes a credible plan to promote longer-term growth. But neither approach alone can heal the global economy without Stimulators and Austerians collaborating on a sustainable path to prosperity. In that respect the summit in Toronto was a missed opportunity, one with potentially painful repercussions if global recovery fails to bloom.