It isn’t surprising that so-called “ambulance economics” has gained mass policy appeal as the global economy descends into madness. The battlefield, after all, is no place for quiet research and careful study. But even the most pressing humanitarian disasters could use a little “clinical economics” to help decision-makers better chart out the way forward. Recent poverty relief efforts in Haiti, for instance, should certainly focus first on the bare essentials of sustenance, sanitation, and security. Once politicians and development professionals are able to stop the bleeding, however, the really critical work actually begins in terms of supporting the long-term prosperity of the country. In that spirit, any path forward should take into consideration the unique historical, geographic, cultural, and economic challenges that lie ahead for the poorest country in the Americas…

It isn’t surprising that so-called “ambulance economics” has gained mass policy appeal as the global economy descends into madness. The battlefield, after all, is no place for quiet research and careful study. But even the most pressing humanitarian disasters could use a little “clinical economics” to help decision-makers better chart out the way forward. Recent poverty relief efforts in Haiti, for instance, should certainly focus first on the bare essentials of sustenance, sanitation, and security. Once politicians and development professionals are able to stop the bleeding, however, the really critical work actually begins in terms of supporting the long-term prosperity of the country. In that spirit, any path forward should take into consideration the unique historical, geographic, cultural, and economic challenges that lie ahead for the poorest country in the Americas…

Haiti and the Dominican Republic: One Island, Two Worlds

By Jared Diamond | Wednesday, January 20, 2010

Why did the political, economic and ecological histories of these two countries — the Dominican Republic and Haiti — sharing the same island unfold so differently? Compared to the Dominican Republic, the area of flat land good for intensive agriculture is much smaller.

Part of the answer involves environmental differences. The island of Hispaniola’s rains come mainly from the east. Hence the Dominican (eastern) part of the island receives more rain and thus supports higher rates of plant growth. Hispaniola’s highest mountains (over 10,000 feet high) are on the Dominican side, and the rivers from those high mountains mainly flow eastwards into the Dominican side. The Dominican side has broad valleys, plains and plateaus and much thicker soils. In particular, the Cibao Valley in the north is one of the richest agricultural areas in the world.

In contrast, the Haitian side is drier because of that barrier of high mountains blocking rains from the east. Compared to the Dominican Republic, the area of flat land good for intensive agriculture in Haiti is much smaller, as a higher percentage of Haiti’s area is mountainous. There is more limestone terrain, and the soils are thinner and less fertile and have a lower capacity for recovery.

Note the paradox: The Haitian side of the island was less well endowed environmentally but developed a rich agricultural economy before the Dominican side. The explanation of this paradox is that Haiti’s burst of agricultural wealth came at the expense of its environmental capital of forests and soils. Haiti’s elite identified strongly with France rather than with their own landscape and sought mainly to extract wealth from the peasants. This lesson is, in effect, that an impressive-looking bank account may conceal a negative cash flow.

While those environmental differences did contribute to the different economic trajectories of the two countries, a larger part of the explanation involved social and political differences — of which there were many that eventually penalized the Haitian economy relative to the Dominican economy. In that sense, the differing developments of the two countries were over-determined. Numerous separate factors coincided in tipping the result in the same direction.

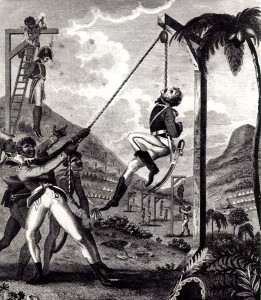

One of those social and political differences involved the accident that Haiti was a colony of rich France and became the most valuable colony in France’s overseas empire. The Dominican Republic was a colony of Spain, which by the late 1500s was neglecting Hispaniola and was in economic and political decline itself. Hence, France was able to invest in developing intensive slave-based plantation agriculture in Haiti, which the Spanish could not or chose not to develop in their side of the island. France imported far more slaves into its colony than did Spain.

As a result, Haiti had a population seven times higher than its neighbor during colonial times — and it still has a somewhat larger population today, about ten million versus 8.8 million. Haiti’s poverty forced its people to remain dependent on forest-derived charcoal from fuel, thereby accelerating the destruction of its last remaining forests. But Haiti’s area is only slightly more than half of that of the Dominican Republic. As a result, Haiti, with a larger population and smaller area, has double the Republic’s population density. The combination of that higher population density and lower rainfall was the main factor behind the more rapid deforestation and loss of soil fertility on the Haitian side. In addition, all of those French ships that brought slaves to Haiti returned to Europe with cargos of Haitian timber, so that Haiti’s lowlands and mid- mountain slopes had been largely stripped of timber by the mid-19th century.

A second social and political factor is that the Dominican Republic — with its Spanish-speaking population of predominantly European ancestry — was both more receptive and more attractive to European immigrants and investors than was Haiti, with its Creole-speaking population composed overwhelmingly of black former slaves. Hence, European immigration and investment were negligible and restricted by the constitution in Haiti after 1804 but eventually became important in the Dominican Republic. Those Dominican immigrants included many middle-class businesspeople and skilled professionals who contributed to the country’s development. Haiti’s burst of agricultural wealth came at the expense of its environmental capital of forests and soils. The people of the Dominican Republic even chose to resume their status as a Spanish colony from 1812 to 1821, and its president chose to make his country a protectorate of Spain from 1861 to 1865.

Still another social difference contributing to the different economies is that, as a legacy of their country’s slave history and slave revolt, most Haitians owned their own land, used it to feed themselves and received no help from their government in developing cash crops for trade with overseas European countries. The Dominican Republic, however, eventually did develop an export economy and overseas trade. Haiti’s elite identified strongly with France rather than with their own landscape, did not acquire land or develop commercial agriculture and sought mainly to extract wealth from the peasants. Finally, Haiti’s problems of deforestation and poverty compared to those of the Dominican Republic have become compounded within the last 40 years.

Because the Dominican Republic retained much forest cover and began to industrialize, the Trujillo regime initially planned, and the regimes of Balaguer and subsequent presidents constructed, dams to generate hydroelectric power. Balaguer launched a crash program to spare forest use for fuel by instead importing propane and liquefied natural gas. But Haiti’s poverty forced its people to remain dependent on forest-derived charcoal from fuel, thereby accelerating the destruction of its last remaining forests.

From the book “Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed” by Jared Diamond, Copyright © 2005. Reprinted by arrangement with Viking, a member of the Penguin Group.