“How much?”

“A lot,” she replies.

“Generic answer” he says, as he heads down the stairs.

The guy has a natural fascination for numbers and quantity. He’s expecting an impressive response. But how much is a lot? And a lot more than what?

Just then, a book drops down on the table in front of her. To put this in context, a lot of books have dropped on the table in front of her these past few months. Well…maybe not dropped, but definitely placed with loving intention.

This time, it’s “A Brief History of Infinity: The Quest to Think the Unthinkable”.

So that’s what he meant. The biggest thing there is.

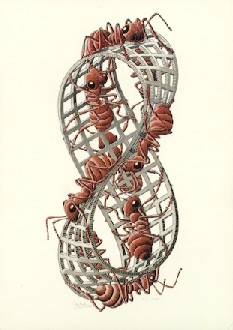

“Forget counting sheep,” he muses. “Staring at this for even a minute could knock me out on the spot.”

She looks at the image again, this time walking around its infinite edges with her beautiful brown eyes. It takes just a few revolutions around Escher’s inspiring geometric forms for her mind to begin to wander, first through the recesses of her own consciousness, and then out into the infinite worlds of physics, philosophy, theology and math.

She looks at the image again, this time walking around its infinite edges with her beautiful brown eyes. It takes just a few revolutions around Escher’s inspiring geometric forms for her mind to begin to wander, first through the recesses of her own consciousness, and then out into the infinite worlds of physics, philosophy, theology and math.

Not surprisingly, this turned out to be a little more stimulating than counting four-legged pillows as they leap rather desperately over a rustic wooden fence. Imagine if restless children were told to “think big” instead of “count sheep” as they lay awake just before bed. Imagine the sort of dreams that might unfold if their tender creative minds were exposed to that sort of higer-order thinking, just as their growing little bodies slip peacefully under the captive veil of sleep.

“Alright, little Jamie. This time, I want you to try and think about how many grains of sand it would take to fill up the entire universe.”

“Alright, little Billy. This time, I want you to think about how you would walk along that never-ending line without falling off.”

Quite simply, it isn’t until you really concentrate on the infinite that your mind begins to wander in these amazingly novel ways. The Hitchhiker’s Guide (not surprisingly) contains the following useful illustration:

“Bigger than the biggest thing ever and then some, much bigger than that, in fact really amazingly immense, a totally stunning size, real ‘wow, thats big!’ time. Infinity is just so big that by comparison, bigness itself looks really titchy. Gigantic multiplied by colossal multiplied by staggeringly huge is the sort of concept we are trying to get across here…”

And so the children think, and sleep, and think some more. And the world is forever changed. Chasing the infinite is an exercise in cognitive futility, but in the end, that’s really the point. When you think about something so unbelievably massive, in contrast, everything else seems so remarkably insignificant. All of your other problems simply dissolve. They become trivial; mere droplets under the bridge.

“But he did this” and “she said that” become obsolete. Arguing over nonsense becomes pointless. Minds grow open to other perspectives, and in the inspiring spirit of Mill, any fundamental disagreements become invaluable stepping stones to an even greater understanding of the world around us (regardless of who was right and why).

And all this from a tiny little picture on the cover of a book, that still, in its infinite greatness, doesn’t quite describe the absolute enormity of her boyfriend’s original question.

“Infinity or not,” she insists. “Love is still the biggest thing there is.”

And for him, that answer was more than enough.