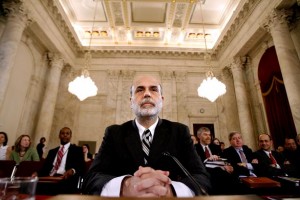

For all its flaws, one of the great strengths of the American political system is the degree to which competing perspectives fight to the death in Washington’s marketplace of ideas. A perfect example is the recent exchange between Senate Banking Committee member (and Baseball Hall of Famer)Â Jim Bunning and his monetary nemesis Fed Chairman Bernanke on the eve of a controversial re-nomination…

For all its flaws, one of the great strengths of the American political system is the degree to which competing perspectives fight to the death in Washington’s marketplace of ideas. A perfect example is the recent exchange between Senate Banking Committee member (and Baseball Hall of Famer)Â Jim Bunning and his monetary nemesis Fed Chairman Bernanke on the eve of a controversial re-nomination…

Bunning Statement On The Re-Nomination Of Ben Bernanke To Be Chairman Of The Federal Reserve

Senate Banking Committee on Thursday, December 3, 2009

Four years ago when you came before the Senate for confirmation to be Chairman of the Federal Reserve, I was the only Senator to vote against you. In fact, I was the only Senator to even raise serious concerns about you. I opposed you because I knew you would continue the legacy of Alan Greenspan, and I was right. But I did not know how right I would be and could not begin to imagine how wrong you would be in the following four years.

The Greenspan legacy on monetary policy was breaking from the Taylor Rule to provide easy money, and thus inflate bubbles. Not only did you continue that policy when you took control of the Fed, but you supported every Greenspan rate decision when you were on the Fed earlier this decade. Sometimes you even wanted to go further and provide even more easy money than Chairman Greenspan. As recently as a letter you sent me two weeks ago, you still refuse to admit Fed actions played any role in inflating the housing bubble despite overwhelming evidence and the consensus of economists to the contrary. And in your efforts to keep filling the punch bowl, you cranked up the printing press to buy mortgage securities, Treasury securities, commercial paper, and other assets from Wall Street. Those purchases, by the way, led to some nice profits for the Wall Street banks and dealers who sold them to you, and the G.S.E. purchases seem to be illegal since the Federal Reserve Act only allows the purchase of securities backed by the government.

On consumer protection, the Greenspan policy was don’t do it. You went along with his policy before you were Chairman, and continued it after you were promoted. The most glaring example is it took you two years to finally regulate subprime mortgages after Chairman Greenspan did nothing for 12 years. Even then, you only acted after pressure from Congress and after it was clear subprime mortgages were at the heart of the economic meltdown. On other consumer protection issues you only acted as the time approached for your re-nomination to be Fed Chairman.

Alan Greenspan refused to look for bubbles or try to do anything other than create them. Likewise, it is clear from your statements over the last four years that you failed to spot the housing bubble despite many warnings.

Chairman Greenspan’s attitude toward regulating banks was much like his attitude toward consumer protection. Instead of close supervision of the biggest and most dangerous banks, he ignored the growing balance sheets and increasing risk. You did no better. In fact, under your watch every one of the major banks failed or would have failed if you did not bail them out.

On derivatives, Chairman Greenspan and other Clinton Administration officials attacked Brooksley Born when she dared to raise concerns about the growing risks. They succeeded in changing the law to prevent her or anyone else from effectively regulating derivatives. After taking over the Fed, you did not see any need for more substantial regulation of derivatives until it was clear that we were headed to a financial meltdown thanks in part to those products.

The Greenspan policy on transparency was talk a lot, use plenty of numbers, but say nothing. Things were so bad one TV network even tried to guess his thoughts by looking at the briefcase he carried to work. You promised Congress more transparency when you came to the job, and you promised us more transparency when you came begging for TARP. To be fair, you have published some more information than before, but those efforts are inadequate and you still refuse to provide details on the Fed’s bailouts last year and on all the toxic waste you have bought.

And Chairman Greenspan sold the Fed’s independence to Wall Street through the so-called “Greenspan Putâ€. Whenever Wall Street needed a boost, Alan was there. But you went far beyond that when you bowed to the political pressures of the Bush and Obama administrations and turned the Fed into an arm of the Treasury. Under your watch, the Bernanke Put became a bailout for all large financial institutions, including many foreign banks. And you put the printing presses into overdrive to fund the government’s spending and hand out cheap money to your masters on Wall Street, which they use to rake in record profits while ordinary Americans and small businesses can’t even get loans for their everyday needs.

Now, I want to read you a quote: “I believe that the tools available to the banking agencies, including the ability to require adequate capital and an effective bank receivership process are sufficient to allow the agencies to minimize the systemic risks associated with large banks. Moreover, the agencies have made clear that no bank is too-big-too-fail, so that bank management, shareholders, and un-insured debt holders understand that they will not escape the consequences of excessive risk-taking. In short, although vigilance is necessary, I believe the systemic risk inherent in the banking system is well-managed and well-controlled.â€

That should sound familiar, since it was part of your response to a question I asked about the systemic risk of large financial institutions at your last confirmation hearing. I’m going to ask that the full question and answer be included in today’s hearing record.

Now, if that statement was true and you had acted according to it, I might be supporting your nomination today. But since then, you have decided that just about every large bank, investment bank, insurance company, and even some industrial companies are too big to fail. Rather than making management, shareholders, and debt holders feel the consequences of their risk-taking, you bailed them out. In short, you are the definition of moral hazard.

Instead of taking that money and lending to consumers and cleaning up their balance sheets, the banks started to pocket record profits and pay out billions of dollars in bonuses. Because you bowed to pressure from the banks and refused to resolve them or force them to clean up their balance sheets and clean out the management, you have created zombie banks that are only enriching their traders and executives. You are repeating the mistakes of Japan in the 1990s on a much larger scale, while sowing the seeds for the next bubble. In the same letter where you refused to admit any responsibility for inflating the housing bubble, you also admitted that you do not have an exit strategy for all the money you have printed and securities you have bought. That sounds to me like you intend to keep propping up the banks for as long as they want.

Even if all that were not true, the A.I.G. bailout alone is reason enough to send you back to Princeton. First you told us A.I.G. and its creditors had to be bailed out because they posed a systemic risk, largely because of the credit default swaps portfolio. Those credit default swaps, by the way, are over the counter derivatives that the Fed did not want regulated. Well, according to the TARP Inspector General, it turns out the Fed was not concerned about the financial condition of the credit default swaps partners when you decided to pay them off at par. In fact, the Inspector General makes it clear that no serious efforts were made to get the partners to take haircuts, and one bank’s offer to take a haircut was declined. I can only think of two possible reasons you would not make then-New York Fed President Geithner try to save the taxpayers some money by seriously negotiating or at least take up U.B.S. on their offer of a haircut. Sadly, those two reasons are incompetence or a desire to secretly funnel more money to a few select firms, most notably Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, and a handful of large European banks. I also cannot understand why you did not seek European government contributions to this bailout of their banking system.

From monetary policy to regulation, consumer protection, transparency, and independence, your time as Fed Chairman has been a failure. You stated time and again during the housing bubble that there was no bubble. After the bubble burst, you repeatedly claimed the fallout would be small. And you clearly did not spot the systemic risks that you claim the Fed was supposed to be looking out for. Where I come from we punish failure, not reward it. That is certainly the way it was when I played baseball, and the way it is all across America. Judging by the current Treasury Secretary, some may think Washington does reward failure, but that should not be the case. I will do everything I can to stop your nomination and drag out the process as long as possible. We must put an end to your and the Fed’s failures, and there is no better time than now.

Not to be outdone, see below for Bernanke’s comprehensive (if somewhat unsatisfying) response to the Senator’s inquisition…

Questions for The Honorable Ben Bernanke, Chairman, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, from Senator Bunning:

1. Please provide:

a. Unreleased transcripts of all F.O.M.C. meetings you participated in as a Governor or Chairman.

b. Unreleased transcripts of all Board of Governors meetings you participated in as a Governor or Chairman.

c. Transcripts and minutes of meetings of the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York during your tenure as Chairman of the Board of Governors.

d. Details, including any unreleased administrative notices, on any exemptions granted or denied to Federal Reserve Act sections 23(a) and 23(b) during your tenure as Chairman.

e. Details of all discount window transactions during your tenure as Chairman, including the date, amount, identity of the borrower, details of any collateral posted, explanation of the valuation of any collateral posted, any analysis of the health of the borrower at the time of the transaction, and any legal opinions regarding the transaction.

f. Details of all transactions at facilities created under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act during your tenure as Chairman, including the date, amount, identity of the borrower, details of any collateral posted, explanation of the valuation of any collateral posted, any analysis of the health of the borrower at the time of the transaction, and any legal opinions regarding the transaction.

g. Copies of any swap or other agreements with foreign central banks, legal opinions related to those agreements, and any analysis of the agreements or the need for the agreements.

h. Any economic analysis or policy materials regarding the need for or effectiveness of any Federal Reserve facilities created under Federal Reserve Act section 13(3).

i. Any economic analysis or policy materials regarding the need for or effectiveness of unconventional monetary policy facilities or actions taken during your tenure as Chairman.

j. Any transcripts, minutes, details, legal opinions, economic analysis, phone call logs, policy materials, or any other relevant information from the F.O.M.C., the Board of Governors, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, or other relevant body not provided under the above requests regarding the use of Federal Reserve Act section 13(3) or actions and decisions regarding AIG, Bank of America, Citigroup, Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, General Motors, Chrysler, CIT, or GMAC.

Without addressing every specific item, I believe that the release of much of the information

requested would inhibit the policymaking process or reduce the effectiveness of policy and thus

would not be in the public interest.

Making public the information you request regarding policy deliberations (including meeting

transcripts and related documents) could stifle the Federal Reserve’s policy discussions, limiting

the ability of participants to engage in the candid and free exchange of views about alternative

– 2 –

approaches that is necessary for effective policy. Although transcripts are not released for five

years (and I believe that we are the only major central bank that does make transcripts public),

we provide extensive information about our deliberations, including through Committee

statements, minutes, quarterly economic projections, testimonies, speeches, the semi-annual

Monetary Policy Report to the Congress, and other vehicles.

The detailed information you have requested regarding participation in Federal Reserve’s broad-

based lending programs would significantly undermine the usefulness of such programs. The

critical purpose of these programs is to provide institutions that have temporary liquidity needs

with a means to meet those needs by coming to the Federal Reserve. Releasing the names of

institutions that borrow would stigmatize such borrowing, making firms less willing to come to

the Federal Reserve and so make it more difficult for the Federal Reserve to respond to financial

market strains. Moreover the Federal Reserve has been highly responsible in its use of these

programs. For example, our discount window loans are fully collateralized, and we have never

lost a penny on such operations. Likewise, the loans made under section 13(3) have been fully

secured. We provide extensive information regarding the number of institutions to which we are

lending under each of our credit programs, and the type of collateral we have accepted, on our

website, as well as information on exemptions granted under sections 23A and 23B of the

Federal Reserve Act.

Finally, the release of staff analyses could have adverse effects on Federal Reserve policy. In

order for the Federal Reserve staff to be able to provide its best policy analysis and advice to

policymakers, it is necessary for some staff analysis to be kept confidential for a period of time.

Release of such information could expose Federal Reserve staff to political pressure. Such

pressure could lead the staff to omit more sensitive material from its policy analyses and more

generally might cause the staff to skew its analyses and judgments. That outcome could have

serious adverse effects on Federal Reserve policy decisions, to the detriment of the performance

of our economy.

The Federal Reserve is very transparent. On a weekly, monthly, quarterly, semi-annual and

annual basis, the Federal Reserve provides to the public in-depth and detailed information

regarding its operations, activities and policy decisions. These materials include:

• Weekly Balance Sheets – H.4.1 Release (See December 10, 2009 Release, attached as Ex.

1, tab A) (also available on our public website:

http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_fedsbalancesheet.htm);

• Monthly Transparency Reports (See November 2009 Report, attached as Ex. 1, tab B)(also

available on our public website:

http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/monthlyclbsreport200911.pdf);

• Policy statements released immediately following each FOMC Meeting (See November 4,

2009 Release, attached as Ex. 1, tab C) (also available on our public website:

http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20091104a.htm);

– 3 –

• Minutes of each FOMC Meeting (See November 3-4, 2009 Minutes, attached as Ex. 1, tab

D) (also available on our public website:

http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20091104.pdf);

• Semiannual Monetary Policy Report & Testimony (See July 2009 Report, attached as Ex.

1, tab E)(also available on our public website:

http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/20090721_mprfullreport.pdf);

• Annual audit of the Federal Reserve’s financial statement provided by independent

accounting firm (See Audit, published in Annual Report and attached separately as Ex. 1,

tab F) (also available on our public website:

http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/rptcongress/annual08/pdf/audits.pdf); and

• Voluminous information on policy actions available on our public website:

http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst.htm.

In addition, the Federal Reserve has submitted one statement for the record and testified before

Congress 43 times this calendar year, including:

• Twelve appearances by the Chairman;

• Three appearances by the Vice Chairman;

• Nine appearances by the Governors;

• Twelve appearances by the Staff of the Board of Governors; and

• Six appearances by the Presidents, Vice Presidents and Staff of the Reserve Banks.

Further, the Federal Reserve has already been audited numerous times in 2009, including:

• The Annual Audit (as mentioned); and

• GAO Audits of non-monetary policy, which total 33 to date – 24 completed and 9 in

process (reports of the audits are available on GAO’s website:

http://www.gao.gov/docsearch/repandtest.html).

2. Treasury published the names of banks that received TARP funds without causing a

panic. Why would disclosing the names of companies that borrow at the discount window

or other Fed facilities be different, especially if only released after a time delay?

It is essential that participants in our liquidity programs remain confident that their usage of these

programs will be held in confidence. If borrowers instead fear that market participants and

others may learn about their usage of these programs, then they will be less inclined to borrow,

reducing the effectiveness of the programs for countering pressures in financial markets. This is

not just a theoretical possibility. When the strains in financial markets erupted in August 2007,

– 4 –

banks were quite reluctant to utilize the primary credit program out of concern that their

borrowing would be discovered by market participants and interpreted as a sign of financial

weakness. Indeed, that stigma significantly reduced the effectiveness of the primary credit

program, and prompted the Federal Reserve to establish the Term Auction Facility and other

programs to more directly address liquidity pressures.

3. What was the involvement of the Board of Governors in each transaction by the New

York Fed under Federal Reserve Act section 13(3)? Did the Board materially alter the

terms of any such transaction? Did the Board approve each transaction before the New

York Fed began negotiations? Please provide other relevant information and

documentation.

As required by section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, the Board of Governors considered and

approved, by an affirmative vote of not less than the required number of members, each credit

facility established under the authority of that provision, after making the required determination

that unusual and exigent circumstances existed. Prior to Board of Governors approval of these

facilities, Board of Governors and New York Federal Reserve Bank staff worked together to

structure the proposal that was presented to the Board of Governors for approval. As authorized

by section 13(3), the Board of Governors imposed specific limits and conditions on these credit

facilities as appropriate to the particular facility. Detailed information concerning each of the

credit facilities authorized by the Board under section 13(3) is available on the Board’s public

website.

4. Did anyone, including the White House or Treasury, request commitments from you

surrounding your re-nomination? Did you make any commitments regarding your re-

nomination?

No one has requested any commitments from me in connection with my re-nomination, nor have

I made any commitments other than what I said in my statement before the Senate Banking

Committee that, if re-appointed, I will work to the utmost of my abilities in the pursuit of the

monetary policy objectives established by Congress to promote price stability and maximum

employment.

5. We saw the crowding out of the private mortgage market caused by Freddie and

Fannie’s overwhelming control of mortgages during 2002 to 2006 period. Do you think

there is a danger to allowing an extended public-controlled mortgage market? And what

steps is the Fed taking to reestablish a private mortgage market?

The U.S. mortgage market has had extensive government involvement for many decades,

including Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Federal Housing Administration, Ginnie Mae, and the

Federal Home Loan Banks. That involvement has had important benefits, including the

development of the mortgage securitization market. However, as the placing of Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac into conservatorship shows, the under-capitalization of the GSEs together with the

implicit government guarantee has also imposed heavy costs on the taxpayer. The Congress will

need to address the appropriate role of the GSEs in the future of the mortgage market.

– 5 –

The Federal Reserve’s agency debt and mortgage-backed securities purchase programs stabilized

the functioning of private secondary mortgage markets during the height of the financial turmoil.

These actions also provided significant benefits to primary mortgage markets.

6. Time and energy in macroeconomic analysis is spent attempting to measure business

and consumer confidence. Confidence measures are part of macroeconomic forecasting

and directly impact monetary policy decisions. Likewise, certain market movements

reflect investor confidence or lack of confidence. Gold is at an all-time high because

investors have lost confidence in policymakers’ handling of fiat currencies. How is the Fed

incorporating this market information into its analytical framework? Does the lack of

confidence in fiat currencies have the potential to impact monetary policy?

Gold is used for many purposes, including as a reserve asset, as an investment, and for use in

electronics, automobiles, and jewelry. Thus, fluctuations in the price of gold can reflect changes

in demand associated with any of these uses, as well as changes in supply. In monitoring the

price of gold, the Federal Reserve must attempt to interpret which of these factors is responsible

for its fluctuations at any point in time. One of the ways we do this is by consulting other

indicators of market sentiment. A number of measures of expected future inflation in the United

States, including measures taken from inflation-protected bonds and surveys of consumers and

professional forecasters, have been well contained. Accordingly, increases in the price of gold

do not appear to reflect increases in the expected future of U.S. inflation.

7. Paul Krugman recently wrote about the problem policymakers will face in the future

because of the publi’’s lack of trust. The public backlash regarding what it sees as

unwarranted bailouts of banks is well-known. What is the Fed doing to restore public

confidence and what are the potential negative implications of this lack of trust on the

Fed’s ability to conduct monetary policy?

The public’s frustration with the support provided banks and certain other financial institutions is

understandable. Unfortunately, withholding the support would have resulted in a substantially

more severe economic recession with significantly greater job losses. My colleagues and I on

the Federal Reserve Board are taking every opportunity, including through speeches and

Congressional testimony, to explain to the public the reasons for the Federal Reserve’s actions.

Moreover, we fully support the efforts under way–in particular, strengthening supervision of

systemically critical institutions and developing a regime to prevent the disorderly failure of

systemically important nonbank financial institutions while imposing losses on the shareholders

and creditors of such firms–to reduce the odds that similar support will be needed in the future.

Most critical for the Federal Reserve’s ability to conduct monetary policy is the public’s

confidence in our commitment to achieving our dual mandate of maximum employment and

price stability. The public’s confidence in our commitment should be bolstered by the Federal

Reserve’s swift and forceful monetary policy response to the financial crisis and resulting

recession and by our careful development of tools that will facilitate the firming of monetary

policy at the appropriate time even with a large Federal Reserve balance sheet.

– 6 –

8. What are the limits on the ability of the Fed to engage in quantitative easing?

A central bank engages in quantitative easing when it purchases large quantities of securities,

paying for them with newly created bank reserve deposits, to increase the supply of bank

reserves well beyond the level necessary to drive very short-term interbank interest rates to zero.

The Federal Reserve’s large-scale asset purchases have been intended primarily to improve

conditions in private credit markets, such as mortgage markets; the increase in the quantity of

reserves is largely a byproduct of these actions. In any case, while large-scale asset purchases

can help support financial market functioning and the availability of credit, and thus economic

recovery, excessive expansion of bank reserves could result in rising inflation pressures.

Congress has given the Federal Reserve a dual mandate to promote maximum employment and

stable prices. That mandate appropriately gives the Federal Reserve flexibility to engage in

quantitative easing to combat high unemployment and avoid deflation while requiring that it

avoid quantitative easing that would be so large or prolonged that it could cause persistent

inflation pressures.

9. In 2002-2005 period, we learned that there is a cost to keeping interest rates too low for

too long. And, we learned it is much more difficult to tighten policy/raise interest rates

after a period of low rates for a long time. Now, you have taken rates to unprecedented low

levels and have also intervened in the mortgage market to produce historic low mortgage

rates. If the US economy bounces back more strongly than currently anticipated, isn’t the

Fed going to have a very tough time raising interest rates without once again impacting

asset prices, especially the housing market?

Federal Reserve policymakers consistently have said, in the statements that the Federal Open

Market Committee releases immediately after each of its meetings and in their speeches, that the

Federal Reserve will evaluate its target for the federal funds rate and its securities purchases in

light of the evolving economic outlook and conditions in financial markets. In that regard, we

announced that we plan to end our purchases of mortgage-backed securities at the end of the first

quarter of 2010; we also announced–and have implemented–a gradual reduction in the pace of

our purchases of such securities. More recently, we made clear that the low target for the federal

funds rate is conditional on low rates of resource utilization, subdued inflation trends, and stable

inflation expectations. As the economy continues to recover, it will eventually become

appropriate to raise our target for the federal funds rate and perhaps take other steps to reduce

monetary policy accommodation. Our continuing communication about monetary policy should

ensure that market participants and others are not greatly surprised by our actions and thus help

avoid sharp adjustments in asset prices.

10. What is the Fed’s current thinking about using asset price levels in monetary policy

analysis? Does the Fed need to anticipate asset bubbles? How can the Fed incorporate

asset prices into their analysis?

Asset prices play an important role in the analysis that underpins the conduct of monetary policy

by the Federal Reserve. We carefully monitor a wide range of asset prices (as well as other

aspects of financial market conditions) and assess their implications for the goal variables that

the Congress has given us, namely inflation and employment. There is a widely held consensus

– 7 –

that central banks should counteract the effects of asset prices on the ultimate goal variables in

this manner.

What is less clear is whether the Federal Reserve should attempt to use monetary policy to “lean

against†bubbles in asset prices by tightening monetary policy more than would be indicated by

the medium-term outlook for real activity and inflation alone. To be sure, the experience of the

past two years provides a vivid illustration of the economic devastation that can be wrought by

an asset price bubble first building up and then bursting. However, three important challenges

would have to be surmounted before tighter monetary policy could be deemed an effective

response to bubbles: First, we would have to be confident in our ability to detect bubbles at an

early stage in their development, given substantial lags in the effects of monetary policy on real

activity and inflation, and the general need for policy to ease in response to the economic

weakness that follows a bubble’s collapse. Second, we would have to be confident that the steps

we took to restrain a bubble in one sector would not cause so much harm in other sectors as to

leave the economy worse off, on net, than if we had not acted. Finally, we would have to be

confident that an adjustment in the stance of monetary policy would be effective in restraining

the bubble itself. It is not clear that these conditions can all be met. And even if they could, we

would still have to determine that some alternative to tighter monetary policy would not be a

better way of responding to the problem.

At this stage, it seems to me that the exercise of regulatory and supervisory policy is likely to be

a more effective approach to addressing issues posed by possible bubbles. Regulators have an

ongoing responsibility to ensure the safety and soundness of the institutions under their care; and

this responsibility implies a need to monitor closely the actions of the firm that might cause it to

be exposed to risks of all types, including those actions that might contribute to the development

of a bubble as well as the possible effects on the firm of the bursting of an asset price bubble. On

balance, therefore, I see a comprehensive and aggressive macroprudential regulatory framework

as likely to be the more promising means of preventing and restraining asset-price bubbles.

All that said, we are giving the issue fresh consideration and attempting to incorporate into our

analysis the lessons of the last two years in this regard.

11. The Fed appears to have coordinated some of its actions in the past year or so with

other policymakers globally. Does the Fed have an obligation to disclose any of these

agreements or coordinated efforts? When the Fed engages in agreements with foreign

policymakers, it has the potential to abrogate its authority. What procedures are in place

to make sure this doesn’t happen? What checks and balances are in place?

In the past year or so, the Federal Reserve has implemented and disclosed policy actions that

have been coordinated with actions taken by policymakers from other countries. These actions

include both the use of central bank liquidity swaps, which have been in place since December

2007, and a reduction in the target for the federal funds rate in October 2008, which occurred in

conjunction with similar rate actions by other central banks. The Federal Reserve announced

these actions in press releases and maintains detailed information with respect to them on our

web site.

– 8 –

The authority for these operations is well established. Policy rate operations clearly fall within

the purview of the monetary policy authority of the Federal Reserve, and the Federal Reserve

Act and longstanding historical precedent support the authority of the Federal Reserve to engage

in swap operations with foreign central banks. We are committed to being as transparent as

possible about our policies and operations without undermining our ability to effectively fulfill

our monetary policy and other responsibilities. The Federal Reserve regularly reports to the

Congress and provides both the Congress and the public with a full range of detailed information

concerning its policy actions, operations, and financial accounts, including arrangements with

foreign central banks such as the liquidity swaps. The Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board

testifies and provides a report to the Congress semiannually on the state of the economy and on

the Federal Reserve’s actions to carry out the monetary policy objectives that the Congress has

established, and Federal Reserve officials frequently testify before the Congress on all aspects of

the Federal Reserve’s responsibilities and operations, including economic and financial

conditions and monetary policy.

12. China is playing a larger and larger role in the growth trajectory of the global economy.

And, China is one of the largest U.S. creditors. Yet, the macroeconomic data from China is

notoriously untrustworthy. How is the Fed conducting its analysis of the Chinese

macroeconomic outlook without access to good data?

While macroeconomic data from China vary in quality, their reliability appears to be improving,

and they now provide a reasonable picture of what is going on. In addition to data from China,

one can also examine Chinese international trade by looking at the statistics produced by its

major trading partners, including the United States. At the Federal Reserve, we monitor a wide

range of Chinese and international data in analyzing Chinese economic and policy developments.

We also closely follow studies on China performed by independent experts, and keep regular

contact with these experts, Chinese academics and authorities, and other U.S. agencies. Through

all these means, we are able to put together a satisfactory assessment of the performance of the

Chinese economy, allowing us to make an informed projection of the country’s economic

outlook and its implications for the U.S. economy.

13. There are a number of macro trends at work that do not seem sustainable — 1) the

substantial accumulation of foreign exchange reserves by surplus/creditor nations, 2) the

escalation of public debt levels in many of the developed market economies, and 3) excess

and deficient savings ratios. These trends do not seem likely to reverse on their own.

Rather, they require tough decisions and compromise on the part of governments around

the world. What is the role of the Fed in this rebalancing process?

To achieve more balanced and sustainable economic growth and to reduce the risks of financial

instability, economies throughout the world must act to contain and reduce global imbalances. In

current account surplus countries, including most Asian economies, authorities must act to

narrow the gap between saving and investment and to raise domestic demand, especially

consumption. As a country with a current account deficit, the United States must increase its

national saving rate by encouraging private saving and, more importantly, by establishing a

sustainable fiscal trajectory, anchored by a clear commitment to substantially reduce federal

– 9 –

deficits over time. By the same token, other countries experiencing large increases in public debt

must implement credible fiscal consolidation policies.

Monetary policy, by itself, is not well suited to address external imbalances. Rather, the goal of

the Federal Reserve, as given to us by Congress, is to pursue maximum employment and stable

prices, not to achieve a particular level of the trade balance. Our role is to ensure the strongest

possible macroeconomic environment, by pursuing the two legs of our mandate, and to work

with fiscal and other policymakers to create conditions that will foster a sustainable external

position. Toward this end, the Federal Reserve participates actively in the G-20 and other

international organizations in a cooperative effort to devise strategies for dealing with these

issues.

14. Please explain the legality of each version of the AIG bailout/loans. How were each of

the loans to AIG collateralized?

Each of the facilities established by the Federal Reserve was authorized and established under

section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act (12 U.S.C. § 343). Section 13(3) permits the Board, in

unusual and exigent circumstances, to authorize a Federal Reserve Bank to provide a loan to any

individual, partnership, or corporation if, among other things, the loan is secured to the

satisfaction of the Reserve Bank and the Reserve Bank obtains evidence that the individual,

partnership or corporation is unable to secure credit accommodations from other banking

institutions.

As described in more detail in the Board’s Monthly Report on Credit and Liquidity Programs

and the Balance Sheet and the reports filed by the Board under section 129 of the Emergency

Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, the–

ï‚· Revolving Credit Facility with AIG is secured by the pledge of assets of AIG and its

primary non-regulated subsidiaries, including AIG’s ownership interest in its regulated

U.S. and foreign subsidiaries;

ï‚· The loan to Maiden Lane II LLC (ML-II) is secured by all of the residential mortgage-

backed securities and other assets of ML-II, as well as by a $1 billion subordinate position

in ML-II held by certain of AIG’s U.S. insurance subsidiaries;1 and

ï‚· The loan to Maiden Lane III LLC (ML-III) is secured by all of the multi-sector

collateralized debt obligations and other assets of ML-III, as well as a $5 billion

subordinated position in ML-III held by an AIG affiliate.

15. The most recent changes to the AIG bailout give the New York Fed equity in AIG

subsidiaries in exchange for loan forgiveness. Under what section of the Federal Reserve

Act are those equity stakes permissible? Please provide any legal opinions on the subject.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York received the preferred equity in the two special purpose

vehicles established to hold the equity of two insurance subsidiaries of AIG in satisfaction of a

1

Upon establishment of the ML-II facility, the securities borrowing facility that the Federal Reserve had established

for AIG in October 2008 was terminated. Advances under this securities borrowing facility were fully collateralized

by investment grade debt obligations.

– 10 –

portion of AIG’s borrowings under the revolving credit facility established under section 13(3)

of the Federal Reserve Act. As a result of the receipt of these preferred interests, AIG’s

borrowings under the revolving credit facility were reduced by $25 billion, and the maximum

amount available under the facility was reduced from $60 billion to $35 billion. The amount of

preferred equity received by the Federal Reserve was based on valuations prepared by an

independent valuation firm. The revolving credit facility continues to be fully secured by nearly

all of the remaining assets at AIG. We continue to believe, based on these valuations and

collateral positions, that the Federal Reserve will be fully repaid.

16. The most recent changes to the AIG bailout give the New York Fed equity in AIG

subsidiaries in exchange for loan forgiveness. Does that indicate that the original “loansâ€

were not really collateralized loans at all, rather they were equity stakes?

No. The revolving credit facility established for AIG in September 2008 was and is fully

secured by assets of AIG and its primary non-regulated subsidiaries, including AIG’s ownership

interest in its regulated U.S. and foreign subsidiaries.

The facility is fully secured by the assets of AIG, including the shares of substantially all of

AIG’s subsidiaries. The loan was extended with the expectation that AIG would repay the loan

with the proceeds from the sale of its operations and subsidiaries. AIG has developed and is

pursuing a global restructuring and divestiture plan that is designed to achieve this objective and

a number of significant sales already have occurred. The credit agreement stipulates that the net

proceeds from all sales of subsidiaries of AIG must first be used to pay down the credit extended

by the Federal Reserve.

17. When the first nine large banks received the initial 125 billion TARP dollars, Secretary

Paulson and you said those nine banks were healthy. Do you now agree with the TARP

Inspector General’s finding that Citigroup and Bank of America should not have been

considered healthy by you and Secretary Paulson?

On October 14, 2008, the Federal Reserve joined in a press release with Treasury and the FDIC

to announce a number of steps to address the financial crisis, including announcing the

implementation of the Capital Purchase Program (“CPPâ€). The first nine banks to receive CPP

funds were selected because of their importance to the financial system at large. In fact, the

SIGTARP report notes that approximately 75 percent of all assets held by U.S.-owned banks

were held by these nine institutions. In addition, these first nine institutions were considered to

be viable, though some were financially stronger than others. The press release referred to these

nine systemically important institutions as “healthy†to indicate that these institutions were

viable and were not receiving government funds because they were in imminent danger of

failure.

18. In 2008, you came to Congress and warned of a catastrophic financial collapse if we did

not authorize TARP. One major problem you predicted was that companies would not be

able to sell commercial paper. However, the Fed has the authority to buy that same

commercial paper and in fact, you created a lending facility to buy commercial paper the

– 11 –

week after TARP was approved. Did the Fed already have plans to implement this facility

before you and Secretary Paulson came to Congress requesting TARP?

The commercial paper market was severely disrupted by the financial crisis, in particular after

Lehman Brothers failed on September 15, 2008, and a large money fund broke the buck the

following day. The Federal Reserve created three facilities in response to the dislocation in

money markets, each of which was designed to finance purchases of commercial paper. The

Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF) was

announced on September 19, 2008. The Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) was

announced on October 7, 2008. And the Money Market Investor Funding Facility (MMIFF) was

announced on October 21, 2008. Your question refers to the CPFF, which was announced the

week after the TARP was approved. All of these facilities helped address strains in money

markets, but they did not replace the commercial paper market completely, and the ability of

firms to sell commercial paper was severely impaired.

On September 18, 2008, Secretary Paulson and I met with Congressional leadership to discuss

the financial situation and explain our view that the global financial system was on the verge of a

collapse. We expressed concern about a number of areas of the economy and financial markets,

including as one example the potential collapse of the commercial paper market. At that time,

the Federal Reserve was working towards developing the AMLF. The Federal Reserve began to

think about constructing the CPFF after observing the effects of the failure of Lehman Brothers

on the commercial paper market. The limitations on the Federal Reserve’s ability to address the

numerous problems that were rapidly emerging in financial markets in the fall of 2008 spurred

the decision by then-Secretary Paulson and me to approach the Congress. As we explained to

Congress, the tools available to the agencies at the time were insufficient to address the serious

stresses facing the financial markets, and action by Congress was necessary to stem the crisis.

19. When you came to Congress last September requesting Congress to pass TARP, did

you have any inclination that those funds would be used for something else besides buying

toxic assets?

Last September, the financial and economic situation was evolving very rapidly. In particular,

the situation–which was already very grave when Secretary Paulson and I began our intensive

consultations with the Congress–had deteriorated sharply further by the time when the

legislation authorizing the TARP was enacted. What was clear from the outset of those intensive

consultations was that the financial system was in substantial danger of seizing up in a way that

had not occurred since at least the Great Depression, and that would have led to an even worse

economic collapse than the one that we have actually experienced. What was not clear, however,

was the strategy that would be most effective in arresting that process of seizing up. Initially, the

strategy that, indeed, received the most attention envisioned using the resources anticipated to be

provided under the TARP to purchase so-called toxic assets off the balance sheets of private

financial institutions, in order to improve the transparency of those balance sheets and to create

the capacity for the private institutions to engage in new lending. Even until Lehman Brothers

fell, the issues plaguing the financial system were closely linked to mortgages, and indeed so too

were the options being considered most seriously. Only after the aftershocks of Lehman’s

failure sapped confidence in the broader set of financial institutions, and interbank markets

– 12 –

seized up, did it become clear to Treasury that providing large amounts of capital to viable banks

would be a superior response to the profound and rapid deterioration that had become the

immediate concern, in substantial part because capital injections could be implemented much

more quickly than asset purchases. These capital injections provided a means to reinforce

confidence in the banking system and its ability to absorb potential losses while retaining an

ability to lend to creditworthy borrowers. The Federal Reserve supported the Treasury’s

decision to adopt the capital-purchase strategy.

20. In your discussions with Ken Lewis about Bank of America’s acquisition of Merrill

Lynch, did you mention the consequences he could face regarding his employment if Bank

of America did not go through with this deal?

As I indicated in my June 2009 testimony before the House Committee on Oversight and

Government Reform, in my discussions with senior management of Bank of America about the

Merrill Lynch acquisition, I did not tell Ken Lewis, the CEO of Bank of America, or the other

managers of the institution that the Federal Reserve would take action against the board of

directors or management of the company if they decided not to complete the acquisition by

invoking a Material Adverse Change (MAC) clause in the acquisition agreement. It was my

view, as well as the view of others, that the invocation of the MAC clause in this case involved

significant risk for Bank of America, as well as for Merrill Lynch and the financial system as a

whole, and it was this concern I communicated to Mr. Lewis and his colleagues. The decision to

go forward with the acquisition rightly remained in the hands of Bank of America’s board of

directors and management.

A recent report by the Special Inspector General for the Troubled Asset Relief Program with

regard to government financial assistance provided to Bank of America and other major banks

confirmed, after review of relevant documents, that there was no indication that I expressed to

Mr. Lewis any views about removing the management of Bank of America should the Merrill

Lynch acquisition not occur.

21. Why was the SEC not notified of the Bank of America/Merrill Lynch deal?

The SEC was fully aware of the deal by Bank of America Corporation (BAC) to acquire Merrill

Lynch. Chairman Cox was present in New York when BAC announced the deal in September

2008. The SEC staff discussed details of the Merrill Lynch acquisition with BAC. The SEC was

not a party to the arrangement by the Treasury, Federal Reserve, and FDIC to provide a ring

fence for certain assets of BAC in mid-January 2009 and therefore had no role in negotiating the

arrangement, though it was informed of the arrangement.

22. When was the first time you became aware of AIG’s potential vulnerability? Did

anyone raise any kind of red flag to you about AIG exploiting regulatory loopholes?

The Federal Reserve did not have, and does not have, supervisory authority for AIG and

therefore did not have access to nonpublic information about AIG or its financial condition

before being contacted by AIG officials in early September 2008, concerning the company’s

potential need for emergency liquidity assistance from the Federal Reserve.

– 13 –

23. According to the TARP Inspector General, the Fed Board approved the New York

Fed’s decision to pay par on A.I.G.’s credit default swaps. What was your role in that

decision, and why was it approved?

I participated in and supported the Board’s action to authorize lending to Maiden Lane III for the

purpose of purchasing the CDOs in order to remove an enormous obstacle to AIG’s future

financial stability. I was not directly involved in the negotiations with the counterparties. These

negotiations were handled primarily by the staff of FRBNY on behalf of the Federal Reserve.

With respect to the general issue of negotiating concessions, the FRBNY attempted to secure

concessions but, for a variety of reasons, was unsuccessful. One critical factor that worked

against successfully obtaining concessions was the counterparties’ realization that the U.S.

government had determined that AIG was systemically important and accordingly would act to

prevent AIG from undergoing a disorderly failure. In those circumstances, the government and

the company had little or no leverage to extract concessions from any counterparties, including

the counterparties on multi-sector CDOs, on their claims. Furthermore, it would not have been

appropriate for the Federal Reserve to use its supervisory authority on behalf of AIG (an option

the report raises) to obtain concessions from some domestic counterparties in purely commercial

transactions in which some of the foreign counterparties would not grant, or were legally barred

from granting, concessions. To do so would have been a misuse of the Federal Reserve’s

supervisory authority to further a private purpose in a commercial transaction and would have

provided an advantage to foreign counterparties over domestic counterparties. We believe the

Federal Reserve acted appropriately in conducting the negotiations, and that the negotiating

strategy, including the decision to treat all counterparties equally, was not flawed or

unreasonably limited.

It is important to note that Maiden Lane III acquired the CDOs at market price at the time of the

transaction. Under the contracts, the issuer of the CDO is obligated to pay Maiden Lane III at

par, which is an amount in excess of the purchase price. Based on valuations from our advisors,

we continue to believe the Federal Reserve’s loan to Maiden Lane III will be fully repaid.

24. Did Fed regulators of Citi approve the $8 billion loan Citi made to Dubai in December

of last year, which was well after the firm received billions of taxpayer dollars? Do you

expect we will get that money back?

With the exception of mergers and acquisitions, the Federal Reserve does not pre-approve

individual transactions of the financial institutions we supervise. Whether Citi is able to recover

this or any other loan it extends is a function of the standards it applied when it underwrote the

loan. Nevertheless, the U.S. government’s recovery of the TARP funds provided to Citi would

not hinge on Citi’s ability to collect on one individual debt, but rather on Citi’s ability to manage

its credit and other risk exposures, which is where the Fed’s supervision has and will continue to

focus. We are currently in discussion with Citi as well as other recipients of TARP funds to

determine the appropriateness of TARP repayment.

– 14 –

25. In response to a question posed by Chairman Dodd, you stated you can give instances

where the Fed’s supervisory authority aided monetary policy. Please do so with as much

detail as possible.

As a result of its supervisory activities, the Federal Reserve has substantial information and

expertise regarding the functioning of banking institutions and the markets in which they operate.

The benefits of this information and expertise for monetary policy have been particularly evident

since the outbreak of the financial crisis. Over this period, supervisory expertise and information

have helped the Federal Reserve to better understand the emerging pressures on financial firms

and markets and to use monetary policy and other tools to respond to those pressures. This

understanding contributed to more timely and decisive monetary policy actions. Supervisory

information has also aided monetary policy in a number of historical episodes, such as the period

of “financial headwinds†following the 1990-91 recession, when banking problems held back the

economic recovery.

Even more important than the assistance that supervisory authority provides monetary policy, in

my view, is the complementarity between supervisory authority and the Federal Reserve’s ability

to promote financial stability. Our success in helping to stabilize the banking system in late 2008

and early 2009 depended heavily on the expertise and information gained from our supervisory

role. In addition, supervisory expertise in structured finance contributed importantly to the

design of the Commercial Paper Funding Facility, the Money Market Investor Funding Facility,

and the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility, all of which have helped to stabilize

broader financial markets. Historically, our ability to respond effectively to the financial

disruptions associated with the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, to the 1987 stock market

crash, as well as a number of other episodes, was greatly improved by our supervisory expertise,

information, and authorities. At the same time, the Federal Reserve’s unique expertise

developed in the course of making monetary policy can be of great value in supervising complex

financial firms.

26. In response to a question posed by Chairman Dodd, you stated “we do not see at this

point any extreme mis-valuations of assets in the United States.†Does that mean you

believe the price of gold is not artificially inflated or out of line with fundamentals? If so,

what does the rise in the gold price signify to you?

Gold is used for many purposes. It is an input into the production of electronics, automobiles,

and jewelry; it is held as reserve asset by governments; and it represents an investment for

private individuals. With fluctuations in the price of gold reflecting changes in demand

associated with any of these uses, as well as changes in supply, it is extremely difficult to gauge

whether or not price changes are consistent with fundamentals. The most recent increases in the

price of gold likely reflect diverse influences, including investor concerns about the many

uncertainties facing the global economy; however, it is also the case that the rise in gold prices

has not been much out of line with the increases in other commodities. According to the

Commodity Research Bureau, after fluctuating in a broad range for the previous 1-1/2 years, the

price of gold has risen 22 percent since early July, while the CRB’s index of overall commodity

prices has risen 17 percent. These increases appear to reflect the recovery of the global

economy, and it is not clear they have been out of line with fundamentals.

– 15 –

27. In response to a question posed by Senator Johnson, you indicated your concern about

the GAO possibly gaining access to “all the policy materials prepared by staff.†What is

your concern about Congress and the public having the same understanding of the issues

surrounding monetary policy decisions as you and the rest of the Fed have?

I think it desirable and beneficial for Congress and the public to have the same understanding of

issues surrounding monetary policy decisions that I and my colleagues on the FOMC have. To

that end, we explain our policy decisions in frequent testimony and reports to Congress as well

as in press releases, minutes, and speeches. In addition, the Federal Reserve makes a great deal

of policy-related data and research material, including materials prepared by Federal Reserve

staff, readily available to the Congress and the public. But, in order for the Federal Reserve staff

to be able to provide its best policy analysis and advice to monetary policymakers, it is necessary

for some staff analysis to be kept confidential for a period of time. If instead this material were

turned over to the GAO, that could ultimately lead to political pressure being applied directly to

the Federal Reserve’s staff. Such pressure could lead the staff to omit more sensitive material

from its policy analyses and more generally might cause the staff to skew its analyses and

judgments. That outcome could have serious adverse effects on monetary policy decisions, to

the detriment of the performance of our economy. Also, investors and the general public would

likely perceive a requirement to turn confidential staff analyses over to the GAO as undermining

the independence of monetary policy, potentially leading to some unanchoring of inflation

expectations and thus reducing the Federal Reserve’s ability to conduct monetary policy

effectively.

28. In response to a question posed by Senator Corker, you stated “On the mortgage-

backed securities, we have a longstanding authorization to do that. I do not think there is

any legal issue.†Please provide the Fed’s legal analysis on the authority to purchase such

securities, particularly those issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which are not full-

faith-and-credit obligations of the United States.

Section 14(b)(2) of the Federal Reserve Act (12 U.S.C. 355) authorizes the Federal Reserve

Banks, under the direction of the FOMC, to “buy and sell in the open market any obligation

which is a direct obligation of, or fully guaranteed as to principal and interest by, any agency of

the United States.†The Board’s Regulation A (12 CFR 201) has long defined the Federal

National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation

(Freddie Mac), and the Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae) as agencies of

the United States for purposes of this paragraph. All mortgage-backed securities (MBS)

acquired by the Federal Reserve in its open market operations are fully guaranteed as to principal

and interest by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae.

29. In response to question posed by Senator Johanns regarding an exit strategy, you said

“The next step at some point, when the economy is strong enough and ready, will be to

begin to tighten policy, which means raising interest rates. We can do that by raising the

interest rate we pay on excess reserves. Congress gave us the power to pay interest on

reserves that banks hold with the Fed. By raising that interest rate, we will be able to raise

interest rates throughout the money markets.â€

– 16 –

In response to a written question I posed to you at the July 22 monetary policy hearing,

you said the Fed at that time had no plans to switch to using the new interest on reserves

power as the means of setting the policy rate. However, in your response to Sen. Johanns

you sound inclined to use the reserve interest rate as the policy rate. Is that correct, and if

so, what has changed in the last few months?

In my written response to the question you posed on July 22, I indicated that the Federal Reserve

currently expects to continue to set a target (or a target range) for the federal funds rate as part of

its procedure for conducting monetary policy. We are already using the authority that the

Congress provided to pay interest on reserve balances, and we anticipate continuing to use that

authority in the future. For example, when the time is appropriate to begin to firm the stance of

monetary policy, the Federal Reserve could increase its target for the federal funds rate. As I

indicated in my response to Senator Johanns, the Federal Reserve could affect the increase in the

federal funds rate partly by increasing the interest rate that it pays on reserves. The Federal

Reserve also has a number of additional tools for managing the supply of bank reserves and the

federal funds rate, and these tools could be used in conjunction with the payment of higher rates

of interest on reserves.

30. In response to a question posed by Sen. Gregg, you stated “it would be worthwhile to

consider, for example, whether regulators might prohibit certain activities. If a financial

institution cannot demonstrate that it can safely manage the risks of a particular type of

activity, for example, then it could be scaled back or otherwise addressed by the regulator.â€

Do you have examples of such activities in mind? Are there some activities that we should

prohibit banks or other financial institutions from engaging in outright?

Congress traditionally has sought to limit the ability of insured depository institutions to engage,

directly or through a subsidiary, in potentially risky activities. Therefore, banking supervisors

have emphasized safety and soundness, banking organizations’ management of risks associated

with their activities, and the adequacy of their capital to support those risks. In that regard, the

Federal Reserve has the authority to take a series of actions to ensure that bank holding

companies and state member banks operate in a safe and sound manner.

As evidenced by the recent subprime lending crisis, even traditional banking activities such as

lending may pose significant risks if not safely managed. These activities do not lend themselves

to general prohibitions, but rather to institution-specific consideration. The Federal Reserve

considers whether a banking organization can effectively manage the risk of its regular or

proposed activities through its ongoing supervisory process as well as its analysis of proposals to

engage in new activities. Going forward, the Federal Reserve will continue to consider actions

under our authority to restrict any activities that present safety and soundness concerns. Such

actions that we might take include, but are not limited to:

ï‚· Imposing higher capital requirements to address weaknesses in asset quality, credit

administration, risk management, or other elevated levels of risk associated with an

activity;

ï‚· Requiring a banking organization to make more detailed and comprehensive public

disclosures regarding a particular activity;

– 17 –

ï‚· Exercising our enforcement authority to limit the overall nature or performance of an

activity, such as by imposing concentrations limits; and

ï‚· Issuing cease and desist orders to correct unsafe or unsound practices.

31. In response to a question posed by Sen. Corker, you mentioned you could provide more

detail about problems at the Fed and the actions you are taking to correct them. What

specific shortcomings have you identified and what specific steps have you taken to address

them?

The financial crisis was the product of fundamental weaknesses in both private market discipline

and government supervision and regulation of financial institutions. Substantial risk

management weaknesses led to financial firms not recognizing the nature and magnitude of the

risks to which they were exposed. Neither market discipline nor government regulation

prevented financial institutions from becoming excessively leveraged or otherwise taking on

excessive risks. Within the United States, every federal regulator with primary responsibility for

prudential supervision and regulation of large financial institutions saw firms for which it was

responsible approach failure.

At the Federal Reserve, we have extensively reviewed our performance and moved to strengthen

our oversight of banks. We have led internationally coordinated efforts to tighten regulations to

help constrain excessive risk taking and enhance the ability of banks to withstand financial stress

through improved capital and liquidity standards. We are building on the success of the

Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (the “stress testsâ€) to reorient our approach to large,

interconnected banking organizations to incorporate a more “macroprudential†approach to

supervision. As such, we are expanding our use of simultaneous and comparative cross-firm

examinations, and drawing on a range of disciplines–economists, market experts, accountants

and lawyers — from across the Federal Reserve System. We are also complementing our

traditional on-site examinations with enhanced off-site surveillance programs, under which

multi-disciplinary teams will combine supervisory information, firm-specific data analysis, and

market-based indicators to identify emerging issues.

32. What was your role in including in the TARP proposal the ability to purchase “any

other financial instrument� Was inclusion of such a provision your suggestion?

Apart from stating the need for it, I was not involved in the negotiations between the

Administration and the Congress on the terms of the TARP. However, the flexibility afforded

the TARP to purchase financial instruments as needed to promote financial stability proved

crucial in allowing a rapid response to the quickly deteriorating financial conditions in October

2008.

33. What was your role in the decision to make capital investments rather than toxic asset

purchases with TARP funds?

It became apparent in October 2008 that the plan to purchase toxic assets was likely to take some

months to implement and would not be available in time to arrest the escalating global crisis.

Following the approach used in a number of other industrial countries, the Treasury made capital

– 18 –

available instead to help stabilize the banking system. The Treasury consulted closely with the

Federal Reserve on this decision.

34. As a general matter I do not think the Fed Chairman should comment on tax or fiscal

policy, so please respond to this from the perspective of bank supervision and not fiscal

policy. Are there any provisions of the tax code that unwisely distort financial institutions’

behavior that Congress should consider as part of financial regulatory reform? For

example, the tax code allows deductions for the interest paid on debt, which may cause

firms to favor debt over equity. Do you have concerns about that provision? Are there

other provisions that influence companies’ behavior that concern you?

The taxation of businesses and households is a fundamental part of fiscal policy. I have avoided

taking a position on explicit tax policies and budget issues during my tenure as Chairman of the

Federal Reserve Board. I believe that these are decisions that must be made by the Congress, the

Administration, and the American people. Instead I have attempted to articulate the principles

that I believe most economists would agree are important for the long-term performance of the

economy and for helping fiscal policy to contribute as much as possible to that performance. In

that regard, tax revenues should be sufficient to adequately cover government spending over the

longer-term in order to avoid the economic costs and risks associated with persistently large

federal deficits. But the choices that are made regarding both the size and structure of the federal

tax system will affect a wide range of economic incentives that will be part of determining the

future economic performance of our nation.

In assessing the lessons of the recent financial crisis, it is difficult to find evidence that the tax

treatment of financial institutions played a role in the problems that developed. In particular, the

tax structure faced by these institutions did not change prior to the onset of these problems and

did not appear to be associated with the buildup of leverage and risk taking that occurred. The

more important remedial steps must be taken in the regulatory sphere, and I have outlined a

comprehensive program aimed at ensuring that a crisis of this kind does not recur.

35. Do you think a cap on bank liabilities is appropriate? For example, do you think

limiting a bank’s liabilities to 2% of GDP is a good idea?

In the policy debate about how best to control the systemic risk posed by very large firms,

restriction on size is one of the solutions being discussed. However, a cap on a bank’s liabilities

linked to a measure such as GDP may not be appropriate. In pursuing a size restriction,

policymakers would need to carefully analyze the metric that was used as the basis for the

restriction to ensure that limits on lines of business reflect the risks the activities present. Broad-

based caps applied without such analysis potentially could limit the banking system’s ability to

support economic activity.

36. AIG still has obligations to post collateral on swaps still in force. Will the Fed post

collateral if the deteriorating credit conditions at AIG or general credit market issues

require it?

– 19 –

No. The Federal Reserve can only lend to borrowers on a secured basis; the Federal Reserve

cannot post its own assets as collateral for a third party. AIG is obligated to continue to post

collateral as required under the terms of its derivatives contracts with its counterparties. AIG

may borrow from the revolving credit facility with the Federal Reserve to meets its obligations

as they come due, including to meet collateral calls on its derivative contracts. AIG itself is

obligated to repay all advances under the revolving credit facility, which is fully secured by

assets of AIG, including the shares of substantially all of AIG’s subsidiaries.

37. If TARP and other bailout actions were necessary because the largest financial firms

were too big to fail, why have the largest few institutions actually been allowed to grow

bigger than they were before the bailouts? Does it concern you that those few institutions

write approximately half the mortgages, issue approximately two-thirds of the credit cards,

and control approximately 40% of deposits in this country?

I am concerned about the potential costs to the financial system and the economy of institutions

that are perceived as too big to fail. To address these costs, I have detailed an agenda for a

financial regulatory system that ensures systemically important institutions are subject to

effective consolidated supervision, that a more macroprudential outlook is incorporated into the

regulatory and supervisory framework, and that a new resolution process is created that would

allow the government to wind down such institutions in an orderly manner. In addition, high

concentrations might raise antitrust concerns that consumers would be harmed from lack of

competition in certain financial products. For this reason, antitrust enforcement by bank

regulators and the Department of Justice would preclude mergers that are considered likely to

have significant adverse effects on competition.

38. On May 5, 2009, in front of the Joint Economic Committee, you said the following

about the unemployment rate: “Currently, we don’t think it will get to 10 percent. Our

current number is somewhere in the 9s” . In November it hit 10.2%, and many economists

predict it will go even higher. This is happening despite enormous fiscal and monetary

stimulus that you previously said would help create jobs. What happened after your JEC

testimony in May that caused your prediction to miss the mark?

At the time of my testimony before the JEC, the central tendency of the projections made by

FOMC participants was for real GDP to fall between 1.3 and 2.0 percent over the four quarters

of 2009 and for the unemployment rate to average between 9.2 and 9.6 percent in the fourth

quarter. As it turned out, we were too pessimistic about the overall decline in real GDP this year

and too optimistic about the extent of the rise in the unemployment rate. Although we indicated

in the minutes from the April FOMC meeting that we saw the risks to the unemployment rate as

tilted to the upside, we underestimated the extent to which employers were able to continue to

reduce their work forces even after they began to increase production again. These additional

job reductions have contributed to surprisingly large gains in productivity in recent quarters and

to the unexpectedly steep rise in the unemployment rate.

39. In his questioning at your hearing, Sen. DeMint mentioned several of your predictions

about the economy that proved inaccurate. For example:

– 20 –

March 28, 2007: “The impact on the broader economy and financial markets of the

problems in the subprime markets seems likely to be contained.â€

May 17, 2007: “We do not expect significant spillovers from the subprime market to the

rest of the economy or to the financial system.â€

Feb. 28, 2008, on the potential for bank failures: “Among the largest banks, the capital

ratios remain good and I don’t expect any serious problems of that sort among the large,

internationally active banks that make up a very substantial part of our banking system.â€

June 9, 2008: “The risk that the economy has entered a substantial downturn appears

to have diminished over the past month or so.â€

July 16, 2008: Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are “adequately capitalized†and “in no

danger of failing.â€

I do not bring these up to criticize you for making mistakes. Rather, it is important to

examine the reason for mistakes to learn from them and do better in the future. Have you

or the Fed examined why those predictions were wrong? Have you or the Fed changed

anything such as your models, forecasts, or data sets as a result? What has the Fed done to

revamp its analytical framework to better anticipate potential macroeconomic problems?

The principal cause of the financial crisis and economic slowdown was the collapse of the global

credit boom and the ensuing problems at financial institutions. Financial institutions suffered

directly from losses on loans and securities on their balance sheets, but also from exposures to

off-balance sheet conduits and to other financial institutions that financed their holdings of

securities in the wholesale money markets. The tight network of relationships between regulated

financial firms with these other institutions and conduits, and the severity of the feedback effects

between the financial sector and the real economy were not fully understood by regulators or

investors, either here or abroad. Our failure to anticipate the full severity of the crisis,

particularly its intensification in the fall of 2008, was the primary reason for the forecasting

errors cited by Senator DeMint.