Commentators often question how recent events in global capital markets could possibly sneak up on the world’s leading economists and policymakers. One possible explanation begins with the premise that the average citizen is reasonably unaware of even the most basic financial and economic concepts – like fractional reserve banking and the time value of money. As a result, generations of otherwise sophisticated individuals have grown up trusting that our economic plumbing and the individuals who manage it are fundamentally sound.

Commentators often question how recent events in global capital markets could possibly sneak up on the world’s leading economists and policymakers. One possible explanation begins with the premise that the average citizen is reasonably unaware of even the most basic financial and economic concepts – like fractional reserve banking and the time value of money. As a result, generations of otherwise sophisticated individuals have grown up trusting that our economic plumbing and the individuals who manage it are fundamentally sound.

From the sophisticated supply chain that furnishes your morning cup of Ethiopian dark roast to the number of travel miles it takes to fly home for the holidays, the financial system reaches seamlessly into virtually every part of our life. It makes transactions easier, redistributes capital where demand is greatest, and creates wealth from what feels like thin air. For precisely that reason, however, it can also be a tremendous source of instability, encouraging speculative euphoria, graft, and occasionally economic collapse.

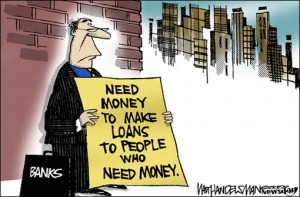

In the wake of this latest in a long series of structural crises, industry titans and policymakers are once again under attack, particularly after sponsoring the most prolific increase in debt the world has ever seen. But the real danger isn’t that they put the entire system at risk for the sake of narrow, short-term, often personal gain. The issue is that too few of us know enough about the way the world works to actually hold them accountable for their actions.

In that spirit, celebrated MIT economist Simon Johnson and his colleagues at the Baseline Scenario have pulled together the following introduction to the financial crisis. There is plenty to bite off and chew – even for the seasoned financial professional – but perhaps it is most valuable as a relatively objective beginners guide to “how stuff works” in our modern, global, post-industrial, debt-addicted, consumption-driven society…

Baseline Scenario

We believe that everyone should be able to understand how the financial crisis came about, what it means for all of us, and what our options are for getting out of it. Unfortunately, the vast majority of all writing about the crisis – including this blog – assumes some familiarity with the world of mortgage-backed securities, collateralized debt obligations, credit default swaps, and so on. You’ve probably heard dozens of journalists use these terms without explaining what they mean. If you’re confused, this page is for you. Over time, we will be adding more explanations and more links to external sources, so check back for updates. (Some of the explanations on this page are simplified and not 100% accurate; their goal is to explain the key concepts to a general audience.)

Contents

Articles on this page

- Securitization, CDOs, and banking capital

- Stock market vs. credit market

- Crises of confidence and bank runs

- Credit default swaps

- Bank recapitalization

- De-leveraging (or, where did all the money go?)

Separate posts

- Currency crisis

- Recession

- Federal Reserve

- Credit default swaps, herald of doom

- Japan’s lost decade

- Interest rates

- Mark-to-market accounting: This one gets a bit technical, but the first part covers accounting in general and mark-to-market accounting

- Risk management and value-at-risk

- “Bad banksâ€

- Sweden

- Is saving good?

- Bank capital, capital adequacy, and tangible common equity

- Convertible preferred shares and the Capital Assistance Program

- Nationalization

- Macroeconomics of the financial crisis

- Comparison of different toxic asset plans (by Mark Thoma)

- Structured finance: This one presumes a basic understanding of what a CDO is.

- Inflation expectations

- Financial innovation

- GDP growth rates and other economic statistics

- Stress tests

- Option and warrant pricing

- Regulatory capital arbitrage (new 5/30/09)

Planet Money collaboration

- This American Life, The Giant Pool of Money (May 2008; 59 min.): If you don’t understand what happened in the housing and mortgage industries in the last decade, this is absolutely the best (and most fun) place to start.

- This American Life, Another Frightening Show About the Economy (October 2008, 59 min.): This one aired on October 4-5 (right after the Paulson plan passed). It explains the basics of the commercial paper market and credit default swaps. However, I don’t agree with the last section on the “stock injection plan;†such a plan is not unequivocally better than an asset purchase plan – it depends on the prices paid in both cases.

- This American Life, Bad Bank (February 2009; 59 min.): Featuring our own Simon Johnson.

- NPR Planet Money podcast (subscribe to the feed or listen online): This is a daily, online radio show (usually 10-25 min.). I don’t always agree with everything their guests say, but they manage to be informative, accessible, and entertaining all at once.

- NPR Morning Edition on reverse auctions: The Planet Money people explain what a reverse auction is and how it might work as part of the Treasury plan to buy troubled assets.

- Planet Money episode on how to track the credit crisis, with Vinny Catalano (his blog is here). Explains Treasury bills, LIBOR, and why they matter.

- Fresh Air interview with Paul Krugman, 10/21/08. Despite being a Nobel Prize winner and a noted polemicist, Krugman does a great job answering some basic questions clearly for non-economist listeners.

- Simon Johnson on Planet Money (12/17/08) talking about the Federal Reserve and the Federal funds rate. The segment begins about 2 minutes in.

- Fresh Air interview with Simon Johnson (3/3/09), mainly talking about the banking crisis and nationalization.

- Paddy Hirsch of Marketplace has a great explanation of CDOs and secondary CDOs (Oct. 2008; 6 min.). Note that it does presume a little familiarity (but nothing you won’t get from the first episode of This American Life or the explanation below).

- Khan Academy YouTube videos on math, physics, banking, and the financial crisis.

- The Big Money article on how the IMF works and where it gets its money.

- Felix Salmon on synthetic bonds and synthetic CDOs, with a step-by-step example.

(I wrote this in August, in another context, for people without a financial background to explain what was going on. Note that it does not describe what has happened since August, which is that we have a liquidity crisis/crisis of confidence as well.)

Even general news accounts presuppose an understanding of terms like “securitization,†“CDO,†and writedown.†So I thought I would provide my own translation.

Historically local banks took deposits from savings account customers and lent money to homebuyers. They paid 1% for the savings accounts and collected 6% on the mortgages, and the spread (5 percentage points in this case) was more than enough to compensate for any homebuyers who couldn’t pay their mortgages. (The numbers are illustrative only.)

Then, as any explanation of the subprime crisis says, banks started reselling and securitizing mortgages. But what does it mean to resell (let alone securitize) a mortgage?

To understand this, you have to look at it from the bank’s point of view. To them, a mortgage is a product. This product gives them a monthly stream of payments – about $1,000 per month for a 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage on a loan amount of $150,000 (numbers are very approximate), but that stream is not guaranteed; the homebuyer might not be able to pay (in which case they might have to renegotiate or foreclose, both of which are costly), or might pay the whole thing early. The price they pay for this product (this stream of payments) is just the loan amount; from their perspective, they are “buying†the stream of payments by paying you the loan amount. The lower the interest rate you get, the higher the price they are paying for your payments.

If Bank A resells your mortgage to Bank B, Bank B buys your payment stream from Bank A in exchange for a lump sum of money. Under stable market conditions, the lump sum that B gives A will be about the same as the lump sum you received from A (in which case A only makes money from various fees). You can also think of this as Bank B loaning you the money for your house, with Bank A acting as an intermediary.

Now, in practice, Bank B (or C, or D, …) is often an investment bank. And Bank B often securitizes your mortgage. This means they take your mortgage and combine it with many (thousands of) similar mortgages. If the mortgages are similar according to certain objective criteria – creditworthiness of borrowers, loan-to-value ratios, etc. – they can be treated as homogeneous. (Something similar happened with corn in the 19th century; certain standards were established for different grades of corn, and from that point bushels of corn from different farms didn’t have to be separately shipped and inspected by buyers, but could be poured together into huge vats.) Now you have a pool of, say, 10,000 mortgages, with about $10 million in payments coming in from borrowers every month. That pool as a whole has a price – the amount someone would pay to get all of those payment streams of that riskiness. In a securitization, the investment bank divides the pool up into many small slices – say 1,000 in this case. Each slice can be bought and sold separately, and each slice entitles the buyer to 1/1,000th of the payments streaming into that pool.

The price of these slices is based on current assumptions about the riskiness of those payments – the riskier those payments are perceived to be, the lower the price anyone will pay for a slice of them. The problem is that at the time those mortgages were securitized, the buyers assumed that housing prices could only go up, and therefore the payments were not very risky; when housing prices began to fall, many more borrowers became delinquent than had been expected. As a result, if you own a slice of that pool, you still own 1/1,000th of the payments coming in, but your expectations of how many payments will come in are much lower than they were when you bought the slice.

(A collaterized debt obligation is a securitization where the slices are not created equal. Some slices are entitled to the first payments that come in each month, and hence are the safest; some slices only get the last payments that come in each month, so when people start defaulting, those are the slides that lose money first.)

This brings us to writedowns and, eventually, to the subject of banking capital. Let’s say you are an investment bank and you paid $1 million for a slice of a securities offering (a pool). You put that on your books as an asset (in the world of finance, a stream of payments coming to you is an asset) valued at $1 million. However, a year later, that slice is only worth $200,000 (you know this because other people selling similar slices of similar pools are only getting 20 cents on the dollar). You generally have to mark your holding to market (account for its current market value), which means now that asset is valued at $200,000 on your balance sheet. This is an $800,000 writedown, and it counts as a loss on your income (profit and loss) statement. And that is what has been going on over the last year, to the tune of over $100 billion at publicly traded banks alone.

The next problem is that, over the last two decades, most of our banks have become giant proprietary trading rooms, meaning that they buy and sell securities for profit. Let’s say you start a bank with $10 million of your own money. That’s your “capital.†You go out and borrow $90 million from other people, typically by selling bonds, which are promises to pay back the money at some interest rate. Then you take the $100 million and buy some stuff (like slices of mortgage pools), which pays you a higher interest rate than you are paying on your bonds. Suddenly you are making money hand over fist. But then let’s say that housing prices start falling, securitized subprime mortgages start plummeting in value, and your $100 million in assets are now only worth $80 million. Since the value of your debt ($90 million) hasn’t changed, you are technically insolvent at this point, because your losses exceed your capital; put another way, the money coming in from your slices of mortgage pools isn’t enough to pay your bondholders.

According to some observers, this is where Fannie and Freddie were until they were bailed out by the U.S. government; by certain accounting rules, they had negative capital.

There is a discussion in my 10/6/08 post that may be helpful.

The discussion above describes how a bank can become technically insolvent – that is, their assets become worth less than their liabilities. However, since the Lehman bankruptcy on September 15, the crisis has moved into a new phase. In this phase, financial institutions are facing liquidity runs, or bank runs, whether or not they are solvent. How can this happen?

To understand this, first you have to understand the time dimension of assets and liabilities. A 30-year mortgage, for a bank, is a long-term asset. They will get a mortgage payment every month for 30 years and, most importantly, they can’t call in the loan before then; that is, they can’t demand that the homeowner pay it back. Bank assets have different maturities, or durations, but a lot of them are medium and long term. On the other side, banks have liabilities with different maturities. For example, deposits (savings accounts) can be withdrawn at any time, so their maturity is essentially instant. Banks also issue bonds: in exchange for some money up front, the bank typically has to pay the bondholder (lender) a fixed monthly payment for some period of time, and then pay back the face value at the end of that period. Banks also engage in many more exotic forms of financing, such as repo agreements, where the bank sells a security to a counterparty for $99 and promises to buy it back for $100 some time later.

The general point, though, is that banks tend to borrow short and lend long. In the classic case, the bank takes money from depositors and loans it out as mortgages. The bank may start out with $10 in capital and $90 in deposits. Then it may lend $80 as mortgages, leaving it $20 in cash. This means it has a leverage ratio (assets to capital) of 10, since it has $100 in assets ($80 in mortgages plus $20 in cash) and $10 in capital. It also has $20 in cash for $90 in deposits, which is a high reserve ratio. But do you see the problem? If every depositor tries to withdraw his money at the same time, the bank can’t call in its mortgages, and there won’t be enough cash for everyone. Now why would this happen, since it is unlikely that everyone will need his cash at the same time? It happens if each depositor starts worrying that his or money might not be safe, and that every other depositor will try to withdraw money, then everyone tries to withdraw his money at the same time.

In ordinary times, bank runs don’t happen. First, the FDIC insures all deposit accounts up to $100,000 per account holder, precisely to prevent this kind of panic. However, in a real bank many of the liabilities are not deposit accounts and hence are not insured. Second, banks can ordinarily borrow money “against†their assets; that is, a bank with $100 in good mortgages can borrow almost $100 from another bank – or, under certain conditions, from the Federal Reserve – by pledging those mortgages as collateral. If the bank’s assets are securities – mortgage-backed securities or CDOs, for example – they can also be used to raise short-term money.

These are no ordinary times, however. The fundamental problem is that all players in the financial system have realized that a bank that is solvent (assets > liabilities) can still be subject to a bank run. Once that happens, Bank A doesn’t want to lend money to Bank B for two reasons: first, Bank A wants to hold onto its cash in case it becomes the target of a bank run; and second, Bank A is afraid that Bank B could be the target of a bank run, and hence is afraid that if it lends to Bank B it won’t get its money back. Like all such panics, of course, this becomes self-fulfilling: because banks don’t want to lend, banks can’t get short-term credit, which makes them vulnerable.

This hits home when a bank has to “roll over†its short-term liabilities. Remember, banks borrow short and lend long. So periodically – almost continuously, in fact – banks have to pay off and replace their short-term liabilities (or just agree with the lender to extend the loan another 30 or 90 days). And even though depositors are insured, all the other liabilities are not insured. The bank run happens when none of the short-term lenders want to extend their loans, and no one else is willing to offer a short-term loan.

In short, this is what has been going on during the last few weeks. The key characteristic of such a crisis is that banks can be hit by bank runs – and go bankrupt – even if their assets are worth more than their liabilities. The Fed has vastly expanded the amount of money it is willing to lend to banks and the range of collateral it is willing to take in an effort to provide the short-term funding banks need to fend off bank runs. In the longer term, though, the Fed is a relatively small player combined to the entire market for short-term credit, and the problem will not go away completely until that market is working properly again.

I’ve had a couple of requests for an explanation of credit default swaps. I’m not sure I can improve on the discussion in the second This American Life episode in our Radio shows section, but I’ll give it a shot.

A credit default swap (CDS) is a form of insurance on a bond or a bond-like security. A bond is an instrument by which companies raise money. A company, say GE, issues a bond with a face value of $100 and a coupon of, say, 6%. This means that if you hold the bond, they will send you $6 per year (6% of $100) until the bond matures (say in 10 years); at they point, they will pay you $100 (the face value). To buy that bond, you pay them about $100. If you pay exactly $100, the yield is 6% ($6 divided by $100). If you pay less, the yield is more than 6%. How much the bond actually sells for depends on how risky you think GE is (the chances that they will go bankrupt and won’t pay you) and on what interest rates you can get for other, similarly-risky bonds in the market. Bond-like securities, like CDOs, are similar in these basic respects.

When you buy a bond, you are taking on two types of risk: (a) interest rate risk and (b) default risk. Interest rate risk is the risk that interest rates in general will go up. If interest rates go up, the value of your bond goes down (bonds are traded in the secondary market), because you are still only getting $6 per year. Default risk is the risk that the bond issuer goes bankrupt and doesn’t pay you back. A CDS is called a “swap†because you are swapping the default risk – but not the interest rate risk – to another party, the insurer. The bond holder pays an insurance premium – typically quoted in basis points, or one-hundredths of a percentage point, per year – to the insurer. In exchange, the insurer promises to pay off the bond if the issuer goes bankrupt and fails to pay it off. At the time the CDS goes into effect, the expected value of the premium payments (a small amount every year) should exactly equal the expected value of the insurance payments (a large amount, but only if the issuer defaults).

This sounds pretty simple, right? So how did CDS become a dirty word? There are two main wrinkles to be aware of.

First, in order to buy a CDS (I call the bondholder in the above example the “buyer,†and the insurer the “sellerâ€), you don’t actually have to own the bond in question. These are over-the-counter derivative contracts, which means they are individually negotiated between buyers and sellers. As a result, CDS became the tool of choice for betting on the likelihood of a company going bankrupt. If you thought the chances of company A going bankrupt were higher than everyone else thought they were, you would buy a CDS on company A. Three months later, when everyone else realized company A was in trouble, the market prices for CDS would have gone up, and you could either sell your CDS to someone else at the higher price, or you could sell a new CDS at the higher price. (In the latter case, you still have your original contract, and you write a new contract with a new buyer.) As a result, there are a lot of CDS out there; estimates are generally around $60 trillion, which means the total face value of the bonds insured is $60 trillion.

Second, CDS are not regulated, and in fact there was a measure inserted into an appropriations bill in December 2000 that blocked any agency from regulating them. Traditional insurance, by contrast, is highly regulated. Insurers have to maintain specific capital levels based on the amount of insurance they have sold; certain percentages of their assets have to be investments of specified quality levels; and, for personal insurance and workers’ compensation at least, private insurance companies are generally backed up by state guarantee funds, which charge a percentage of all insurance premiums and, in exchange, pay off claims for bankrupt insurers. The CDS market had none of that, so a bank could sell as many CDS as it wanted and invest the money in anything it wanted.

So, 2008 rolled around, and bonds started going bad. There were CDS not just for traditional corporate debt, but also for mortgage-backed securities, CDOs, and secondary CDOs. During the boom, when everyone was optimistic, CDS for these exotic products were cheap; when they started failing, the price of CDS shot up, and anyone who had sold these swaps was looking at losses on them. So CDS were one way that losses on subprime mortgages triggered writedowns at other financial institutions. This only got worse as banks, such as Bear Stearns and Lehman, started failing, and people who had sold CDS on their debt faced even larger losses. So the most basic problem with CDS is that the insurers selling them (and many of the companies selling them were not insurance companies) sold them at excessively low prices, and now they are facing major losses.

Second, you have the risk that the insurance companies won’t be able to pay. If a financial institution – say, AIG – sold a lot of CDS based on the debt of a particular company – say, Lehman – there is a risk that it won’t be able to honor all of those swap contracts. In that case, their counterparties – other banks – may be looking at losses they thought they were insured against. If Bank B bought a CDS from Bank C on the debt of Company X, and Company X defaults, Bank B thinks it has a payment coming to it from Bank C; but if Bank C doesn’t have the cash, Bank B won’t get its payment. Even worse, let’s say Bank B bought a CDS from Bank C, and then sold a different one to Bank A. Bank B thinks it is perfectly hedged, and Bank A thinks it has a payment coming. But if Bank C can’t pay out, Bank B may not be able to pay Bank A – and these chains can go on and on and on. So CDS are one of the things that create uncertainty in the banking sector; a bank may look healthy, but it may be counting on CDS payouts from other banks that you can’t see, so you can’t be sure it’s healthy, so you won’t lend to it.

The cumulative effect of CDS is to spread risk, which sounds good, but to spread risk in unpredictable and invisible ways. One of the major reasons why the government refused to let AIG fail – one day after letting Lehman fail – was that AIG was a large net seller of CDS, and if it had defaulted on those swaps no one could predict what the implications would be for the rest of the financial sector. At this point in the financial crisis, it would be a mistake to blame the whole thing on CDS, but they have had the effect of amplifying and spreading uncertainty in ways that have reduced confidence in the financial sector.

If you read the section on securitization above, you know a little bit about what a bank balance sheet looks like. There are assets (things you have that are worth money and that you theoretically could sell for cash) and liabilities (money you owe other people), and hopefully your assets are more than your liabilities. The difference is your “stockholder’s equity.†So your assets equal your liabilities plus your equity.

Think about it this way: in order to buy assets (or loan money, which creates assets), a bank needs to get cash from somewhere. It has two ways of raising cash. First, it can borrow money and promise to pay it back: those are liabilities. Second, it can sell ownership shares in itself. If you buy those shares, the bank does not say it will give you your money back; it says that you are entitled to some percentage of the bank as a whole. This is what it means to own stock in a company.

If times are good, the assets grow in value while the liabilities stay constant, so stockholder’s equity goes up. Roughly speaking, this means that if the bank sold all its assets and paid off all its liabilities, there would be more money left for the stockholders than they put in. Of course, if times are bad, stockholder’s equity goes down. If it goes down too far, assets are not much more than liabilities, and the bank risks becoming insolvent.

In this case, raising more money through loans (liabilities) does not really help, because it just increases the leverage ratio. (If I have $100 in assets and I owe $99, then borrowing $10 just means I have $110 in assets and I owe $109.) Instead, banks need to increase their stockholder’s equity by selling more shares in themselves. This is a recapitalization. To simplify things a little, this means that they sell more ownership shares in themselves in exchange for cash; that cash makes stockholder’s capital go up, and the bank has more cash, yet it doesn’t have more debts. The downside is that the current shareholders have been diluted. If a bank has $5 billion in stockholder’s equity and it raises $5 billion by selling shares, the old shareholders now only own half of the bank, which may make them unhappy.

The above is a simple example. In practice, new capital is usually added in the form of preferred shares, which are somewhere between ordinary (common) stock and debt, but closer to stock. Preferred shares often pay a dividend, like a bond, meaning that the new investor gets a fixed amount of money each year; preferred shares also often are convertible to common stock under some terms, meaning that the investor can trade them in for common stock (if the common stock increases in value, you would want to do this). But if the bank goes bankrupt, preferred shareholders get their money back only after the bondholders, so preferred stock is a good deal more risky (for the investor) than bonds. Conversely, if a bank raises money by selling preferred stock, lenders will consider the bank safer (because it has more cash) and will be more likely to lend to it. In all the recapitalizations you are seeing these days, whether the investor is Warren Buffett, Mitsubishi UFJ, the UK government, or the US government, you will see some version of this structure.

This is a fairly common question. If banks are taking losses by writing down hundreds of billions of dollars, is someone else gaining hundreds of billions of dollars? Or is money just vanishing? Planet Money took a stab at this with Satyajit Das, but I thought I could help clarify it with a simple example.

Let’s say the economy has just three people: Developer Danny, Homebuyer Harry, and Banker Bonnie. At time zero, Developer Danny has $200,000, Homebuyer Harry has $40,000, and Banker Bonnie has $360,000, so there is a total of $600,000 in the world. Developer Danny sees that the housing market is hot, so he spends his $200,000 buying land and building a house that has a market price of $400,000. He then sells the house to Homebuyer Harry. Harry makes a 10% down payment of $40,000 and borrows $360,000 from Banker Bonnie.

Now, in time one, Danny has $400,000 in his pocket, up from $200,000. He has that $200,000 profit because he has created that much value – he took stuff that was only worth $200,000 and he made it worth $400,000. Good for him. Harry has a $400,000 house and a $360,000 mortgage, so his net worth is $40,000; Bonnie has a $360,000 mortgage asset. There are $800,000 in the world now, thanks to Danny. Danny has $400,000 he can use to build more houses or buy expensive sports cars; Harry can get a home equity loan to renovate his kitchen, because he has positive equity; and Bonnie can get more loans against her $360,000 asset.

Then, in time two, housing prices crash, so the house is only worth $300,000. Let’s say Harry had an Option ARM mortgage and he can’t make his payments, so Bonnie forecloses on him. Now Harry has nothing; Bonnie has a house that is only worth $300,000; and Danny still has $400,000. There are only $700,000 in the world. Harry can’t spend money, because he doesn’t have any; even after Bonnie resells the house, she doesn’t have as much lending capacity as she used to. (Even if Harry did make his payments, Bonnie’s mortgage would still be worth $360,000 to her, but Harry would have negative equity for a long time, so there would still only be $700,000 in the world.)

What happened? The fact that housing prices went up meant that there was more money. (Imagine the house already existed, and someone bought it for $200,000 and later sold it for $400,000.) But there wasn’t actually more stuff – as the price goes up or down, a house is still a house. As prices come down, there is less money to go around. What makes it particularly painful is the phenomenon of leverage. Because people, and banks, are able to borrow considerably more than their net worth, falls in asset prices are magnified. This can create a vicious cycle. For a highly leveraged financial institution, losses in one asset category can force you to raise cash by selling other assets, causing their prices to go down. For a homeowner, if you hadn’t borrowed money, the fall in the value of your home wouldn’t necessarily affect your consumption. But if your consumption is based on your ability to borrow, then a small fall in your house’s value can cause a large drop in your discretionary income.

There are many variations of my little example – for example, imagine that Bonnie sold half of the mortgage to Hedge Fund Helen; or imagine that Danny invested his money in Hedge Fund Helen, so he gets hurt, too – but I think this demonstrates the basic principle.

Note: I stopped adding new Beginners articles to this page and started adding them as new posts. Links to these posts are available at the top of this page, or you can find them by clicking on the Classroom category to the right.